An interview with the subjects of this impassioned documentary, and with the filmmaker who revisited the controversial case of “The New Jersey Four”

Featured image from left: Venice Brown, Terrain Dandridge, Patreese Johnson and Renata Hill. Courtesy of Indiewire.

Author | Demitra ‘Demi’ Kampakis | Film Editor

“I mean, when it becomes a matter of your friend not being able to breathe, then you realize it’s us or him.”

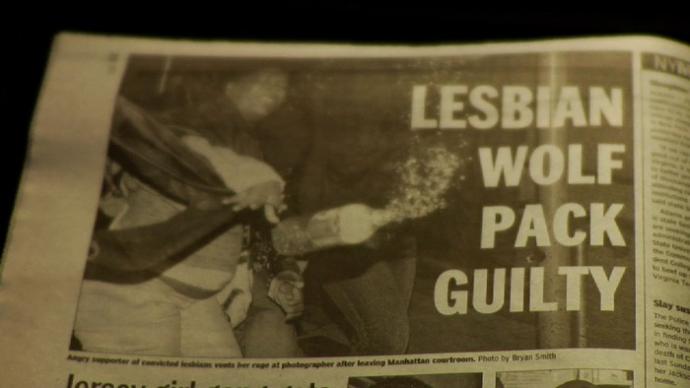

“Attack of the Killer Lesbians.” Believe it or not, this isn’t the title of a 1970s pulpy exploitation film, but an actual headline featured in a 2007 New York Post article. Unfortunately, it is just one of the countless number of egregious newspaper “reportings” that covered the now infamous case which serves as the subject of blair dorosh-walther’s new documentary “Out in the Night.” The film follows the story of Venice Brown, Terrain Dandridge, Renata Hill and Patreese Johnson, four African American lesbians who became known as the “New Jersey Four” after they defended themselves against an assault on the streets of New York City’s West Village. Late one night in August 2006, these Newark-native women were walking through the West Village when a man (29 year old Dwayne Buckle) standing in front of the IFC Center movie theater made a lewd remark; the first of a series of profane and unwanted sexual advances in which these women were the targets of. Angry that they refused his advances by asserting their sexuality, Buckle’s verbal harassment quickly escalated into a physical altercation. This frenzied four-minute brawl was captured on surveillance video by IFC cameras, and ended with Buckle in the hospital and the women in jail. That such a brief yet violent incident took place in front of an art-house theater in the late hours of the night and was captured via grainy security footage represents an interesting collision between objective and subjective truth—one that blair’s documentary explores; as it challenges us to consider how race, class, sexuality, and gender expression influence society’s perception of violence. In short, “Who has the right to self-defense?”

Shortly after the film’s NY premiere at The Human Rights Watch Film Festival, I had the chance to interview dorosh-walther, Renata Hill, and Patreese Johnson; who served the longest sentences after pleading not guilty, and for whom the film largely centers on. “At first I didn’t know it was going to take me seven years to complete this project,” noted blair, “but right after the incident occurred, the media coverage was just outrageous. Nobody knew exactly what had happened, but that didn’t stop the outpour of ridiculous headlines. Many LGBTQ organizations and individuals would meet and hold discussions in which they voiced their concerns over these homophobic headlines: they wanted to know how to go about protecting yourself when you don’t feel comfortable going to the police. But what really did it for me was this one New York Times article that struck me in its gross inaccuracy…you know, there were many ludicrous and misinformed articles written on the case, but this was The New York Times! It all felt really weird and wrong, so I became an advocate during the first two years of the case. And interestingly enough, once these women’s appeals trials began approaching in 2008, I noticed that there was almost no media coverage whatsoever (barely a few articles). That definitely weighed on me, and reignited my interest. So that’s when I started reaching out to these women and their families.”

Shedding light on the bizarre circumstances surrounding the August 2006 incident, “Out in the Night” chronicles the troubling, infuriating and unjust legal aftermath that resulted in heinously long prison sentences for these four women that were certainly fueled by the media’s attempts to exploit and scandalize their act of self-defense. “At first none of us knew the extent to which things would escalate in such a dangerous and frightening way. But once the man started advancing towards us and actually inflicting physical harm through choking, pulling out our hair, etc., then the automatic survival instincts kicked in. I mean, when it becomes a matter of your friend not being able to breathe, then you realize ‘it’s us or him’,” noted Johnson during our interview, as she reflected on that critical moment of desperation that left her behind bars for a dozen years.

The film also highlights numerous examples of legal incompetency and courtroom corruption on behalf of the prosecution team and judge—injustices that include yet extend far beyond withholding evidence and denying bail. In fact, at one point in the film it is revealed that these women were charged with counts of gang violence, for no other reason than the simple fact that ‘gang’ is the legal term used for a group of four or more individuals. It didn’t matter that none of these women had any gang affiliation whatsoever—or that two were mislead into pleading guilty through the judge’s incorrect explanation of the term “accessory”—because the massive wave of media hysteria had already cemented. In the eyes of NYC journalists, these women were in fact ‘gang members’ part of a “Lesbian Wolf Pack.” dorosh-walther notes, “It was the perfect storm.”

And then there’s the police officer that responded to the case and agreed to be interviewed for the film. Throughout the documentary his calm demeanor felt wholly reassuring, and there was a legitimate credibility in the way he articulated the incident with such objective neutrality noting how both parties contributed to the violent episode. Yet it isn’t until the last moments of the film—where his call to 911 dispatch is revealed—that we discover the extent to which he fabricated his entire interview and testimony. Contrary to the officer’s official statement that Buckle had suffered critical injuries resulting from a stab wound inflicted by Patreese Johnson, his 911 call tells a different story. “Not gang activity, it was a tiny little pen knife he got cut with…not even blood on the scene.” Oh, and did I mention that this particular dispatch call was also never admitted as evidence?!

Throughout the film, dorosh-walther cleverly weaves Buckle’s court testimony (narrated through transcripts read by an actor) claiming self-defense with surveillance footage that shows him physically attacking the women, and the film’s use of animation serves as a nice visual tool in picking apart the camera footage frame-by-frame. Despite a few moments that feel somewhat unbalanced, subjective and biased, the documentary as a whole makes a point to emphasize that no one is a victim. Rather than portraying these women as heroes, dorosh-walther is concerned with humanizing them as a means of exposing the harsh realities of a failed justice system, the devastating impact of gender-based harassment, and the media’s accountability in producing a climate of blame and guilt that is further amplified by a subculture of racism, misogyny, and homophobia. By contrasting footage of tender family moments and the emotional toll faced by loved ones, dorosh-walther smartly illuminates the incompatibilities between private and public narratives. A refreshing indictment on sensational media, “Out” boldly reveals the lack of empathy and protection for targets of socialized crimes; and the gross power by which a public persona can quickly reduce the nuances, complexities, and humanity of an individual. Although the film could have spent less time dissecting the incident itself—and instead address the years of courtroom battles and legal corruption with greater attention—it does include powerful commentary on the effects of incarceration and the policing of gender in the prison system. The doc’s occasional overreaching attempts to link the case to broader issues of gender discrimination can be forgiven because it ultimately succeeds in fostering critical dialogue surrounding issues of resistance and self-defense facing black women. There is a passionate sense of immediacy in the way dorosh-walther gives voice to LGBTQ people of color who continually face this type of institutional harassment and slander.

“There’s certainly the hope that this film will help mobilize reform within the media and legal system, but I sort of feel like the realistic thing that will happen will be the onset of debate. Journalists will have varying responses because this case is so nuanced. But I’m cautiously optimistic that the legal responses to self-defense will be re-visited with scrutiny because much of this case has to do with the context for why these women felt so threatened that night,” remarked dorosh-walther. “I think we still have a long way to go, because this isn’t the first documentary out there that deals with these issues and I hope it isn’t the last. Especially with the cases that get overlooked, we need more. People to stand up and speak about what’s going on. And I think that we did what we needed to do,” adds Renata, who concluded with this powerful remark: “It’s hard not to feel angry and cynical after an ordeal like this, but I really try to focus my emotional energy on growing closer with my son and not taking my freedom for granted. One thing that this experience definitely taught me though is that there’s no such thing as a ‘safe space’. After all, we went to the West Village for a carefree night on the town—to proudly embrace who we were—and never expected the sad irony of a homophobic bashing in such a gay-friendly neighborhood.”

With its world premiere at last month’s Los Angeles Film Festival, “Out in the Night” has also been screened at San Francisco’s Frameline LGBT Film Festival, and will play at this month’s OutFest in LA.

Follow Demi:

Twitter: @DemionFilm

Facebook: facebook.com/demionfilm