The concept of Cyberfeminist art could mean something different to everyone. What does it look like to “disrupt” the digital, and why are women in such a unique position to do this? Our bodies are constantly on display in every form of media imaginable. Spectators on Instagram pick women’s bodies apart for sport. Our selfies can be stolen and used to advertise porn sites. Random men all over the world can see our Facebook profiles and send us unsolicited messages. As a sex worker, I know that clients will sometimes use reverse image search on my ad photos to find my Facebook profile. Our inherent visual vulnerability has created a consistent theme in digital art of women using their bodies to navigate conversations around visibility.

“These questions of how digital disruption effect those of varying class and racial backgrounds is important as more young women use social media to curate a persona that matches their inner self (or the self they want to be).”

Such a conversation took place last week at A.I.R Gallery in Brooklyn, a space dedicated to the advancement of women artists. At Performing Digital Disruption, an array of women artists from different backgrounds and cultures working within a cyberfeminist framework discussed their art practices.

Daria Dorosh is a co-founder of A.I.R and has been working with these themes since the early ‘70s. Her most recent work, The Art of Sleep, examines sleep time as a space that has not yet been taken over by digital entities; our dreams are completely individual and fully connected to our own bodies. Dorosh creates ornate clothing and jewelry to be worn during bedtime. She believes that what we wear to bed influences one’s self image while they sleep. Her pieces exist “IRL,” her work is sculptural and tangible yet it deals with the idea of the digital world as an invasion on the female body.

Amelia Marzec is another artist who chooses to work with tangible objects in order to explore themes surrounding digital disruption. I was most struck by a piece from 2005 called The Gender Anarchy Project. Marzec created a custom door with an interactive sign where the iconography changed from male/female in order to give the participant the experience of a gender-neutral space. More recently Marzec has created The New American Sweatshop where electronic waste is repurposed to create new communication devices. This is accompanied by a training module kit, which empowers people to learn how the technology they use everyday actually works.

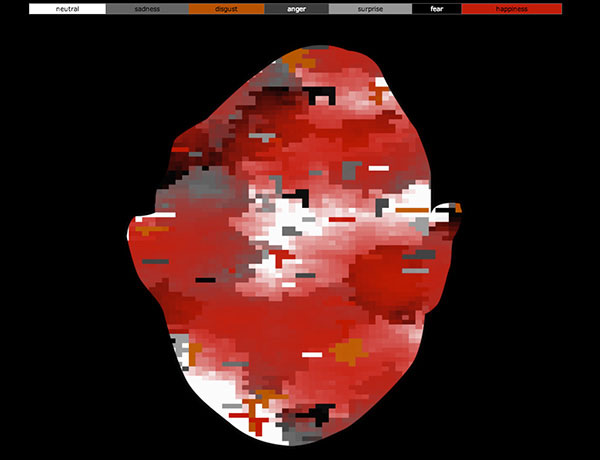

Bang Geul Han chooses to work completely within digital mediums. A South Korean immigrant, Geul Han spoke during her talk about coming to the U.S. and feeling completely isolated by language barriers, and so she turned to the internet and digital mediums to communicate her emotions. Her 2013 project Interior Surface uses a commercial facial expression analysis service, NViso, to analyze the emotions expressed in her selfies. Emotion is analyzed in seven categories (neutral, anger, disgust, surprise, fear, happiness) and fed into a spreadsheet and remapped onto the face that now becomes a camouflage mask of feelings with each color in the pattern representing a different emotion. The camo pattern recalls the act of hiding and even of being at war with the self and the way others perceive us.

Marie Tomanova started her practice as a painter while in her home country of the Czech Republic. After experiencing discouragement and harassment from the male dominated faculty, she immigrated to the U.S. and now works only within photography. In the tradition of feminist artists before her, Tomanova takes self-portraits of her naked body in various positions and landscapes. The bulk of her talk focused on how these self-portraits function on social media, mainly Instagram. Tomanova is concerned with censorship of the female body and is a proponent of the #freethenipple movement. She tracks which tags and what position of her body will cause her photos to be removed from her account and reported.

During the Q&A portion of this talk, the artists discussed the power of the female experience and body to disrupt notions of digital decorum. Dorosh spoke about women as pioneers of this art form, and yet now the discourse seems to be dominated by male artists. There was also a discussion around persona and how we create a curated image of ourselves using social media. Tomanova’s concern with censorship of the female body particularly interested me. I wonder how the issues discussed play out for more marginalized bodies. After all, with the exception of Bang Geul Han, every artist was a white cisgender woman. Would Tomanova’s art practice resonate for a woman of color, a fat woman, a disabled woman? Does visibility necessarily always correlate to empowerment?

I can’t help but think about this in relation to sex work. The advent of the Internet allowed for escorts to work more anonymously and undercover. However, within the last five years even the sites that sex workers use to advertise their services have become unsafe, as authority/police presence has slowly turned the Internet into another site of constant surveillance. Many workers have gone back to the streets or to meeting clients in person. So digital visibility for sex workers is actually quite dangerous and not feasible. Our empowerment does not look like Tomanova’s. Not to say that every woman should find liberation in the same way. These questions of how digital disruption effect those of varying class and racial backgrounds is important as more young women use social media to curate a persona that matches their inner self (or the self they want to be).