Founded by Jiun Kwon, Katherine Tom, Tsige Tafesse, Jazmin Jones, and Sonia Choi, BUFU (short for By Us For Us) is comprised of a cadre of five queer, femme, Black and Asian multidisciplinary artists and organizers strategizing to activate marginalized Black and Asian communities around POC solidarity. BUFU works to highlight and re-engage cultural contact between Black and Asian communities, particularly via an Afro-Asiatic integrative experience that draws from myriad sociopolitical movements heralded by both celebrated and less well known activists, ranging from Pan African traditions to Yuri Kochiyama’s advocacy of Black nationalist freedom fighters. BUFU acknowledges the global, deep-seated, and ancient connection between Black and Asian communities; a history that has been forced into obscurity via state-sanctioned violence (long before the shooting death of Akai Gurley, an unarmed black man, by Chinese-American NYPD officer, Peter Liang) and an investment in whiteness that many Asians immigrating to this country are confronted with when racism charges them to assimilate and conform to American standards of acceptability. The urgency in this work is what BUFU recognizes as a need to reconnect Black and Asian communities, centering them not only within a political framework, but a spiritual ethic that gives voice to what BUFU member Tsige describes as a “very recent” discord between Blacks and Asians: “it’s not inherent in our relationship.” She continues: “There is not much of a shared language surrounding the historical, cultural and highly sociopolitical Afro-Asian relationship.”

“It’s so clear that we [Blacks and Asians] are intertwined aesthetically, a reason we keep ending up marginalized in these communities together…it’s no coincidence.” – Tsige Tafesse

Using the tools of multimedia and film arts to offer a safe space and platform for the difficult, long overdue conversations about Afro-Asiatic solidarity as a model for greater POC solidarity, BUFU uses art to build coalitions and further community organization in the U.S. and abroad. Most people, racial identity notwithstanding, are unaware of the link between Black and Asian communities. Tsige notes: “It’s so clear that we [Blacks and Asians] are intertwined aesthetically, a reason we keep ending up marginalized in these communities together…it’s no coincidence.” It’s also important to note that though the collective met in college on the East Coast and is based out of New York, three of the five members of BUFU are from the West Coast. Tsige, who identifies as Habesha, an anti-nationalist term to honor a mixed tribal history of her family’s native Ethiopia, has stated she does not invest in the idea of nation states designed to oppress and separate people. (Author’s note: agreed.) The West Coast progressive political ethic encourages a lot more inter-POC conversations than in NYC. From Seattle to Los Angeles and Oakland, Asians and Blacks have found themselves grouped closely in under-resourced, low-income communities, and systemically deprived in the same ways. Though experiences of being denied access to greater economic opportunities look a lot different given white supremacist notions of the model minority versus the completely vilified black one.

Part of the beauty of BUFU is their willingness to proffer a space for folks to address the tensions between these two communities, to create space for the elephants in the room; true to a queer theoretical and conceptual framework in which heated debate is engaged in compassionately. Sonia mentions a particularly intense, discomforting discourse at a political organizing event around POC discord for the documentary film Black Hair in which the polarizing relationship between Korean small distributors and black consumers in the extremely lucrative international and domestic hair care markets was discussed. Tsige admits, “it’s not a cute conversation, it’s contentious. There’s a lot of power and privilege at stake. It’s discord in the service of white supremacy.” To contend with the tension that arises in the course of difficult conversation, BUFU holds group healing for community members to grieve and mourn injustices together, share experiences, and have their experiences upheld in a safer space. At the same time, the joy sometimes sifted from struggle is present and BUFU provides outlets for creative and artistic collaboration be-tween community members. This past June, the collective rolled out a series of events for a month of Black and Asian Futurity, including a future building workshop, partnering with organizations that serve youth of color with mentorship, workshops, and day long intensives.

Beyond Korean rapper Keith Ape’s notoriously contentious but popular and acclaimed music video for his trap ode “It G Ma,” BUFU affirms that the cultural appropriation of hip hop in Korea is a continuation in the line of mainstream exploitative ways in which black creative thought and expression are used — even by other POC. Which begs the question: blackness is en vogue, but are black people benefitting due to its proximity to the commercial viability conferred by increased exposure and commodification of black cultural product? When they aren’t dismantling colonialist divisions between POC as a means to realize revolutionary justice, foster movement building and solidarity, and facilitate cultural dialogue that explores the history of Afro-Asian solidarity, BUFU is producing projects all over the world. One such project in the works is a documentary slated for release in 2017. They’ve already completed interviews with folks in Southeast Asia and China, and shot at SXSW. This year alone they produced 112 events in one month. I dare say that is not just contemporary artists making creative trouble — it is strategy. It’s not lip service at poetry cafes rabble-rousing toward an equitable future, it truly is art by us for us, by the people.

At the core of BUFU’s work in facilitating living archives and Afro-Asian cultural exchange is the query: While art boasts the ability to wage cultural war, to fight against the dominant trends of the patriarchal day, is it capable of waging community? Radically loving community? The nexus to a freedom that is indelibly driven by a collective struggle to realize interdependence as a path to social justice and political liberation? Art has proven its knack for propagating leftist sensibilities, but is it truly accessible, and what are the limits or parameters to that accessibil-ity? Who is then an artist, where are the lines drawn, and who drew them? Why should there be any? The painful tenderness that proffers and accompanies most creations, whether that be of a person, an artwork, or the co-creation of reality whenever we wake up in the morning — sometimes hungry and broke, loving on an empty stomach — is what undergirds BUFU’s facilitation of safer spaces for Blacks and Asians to have difficult conversations, for divisions to be addressed and an incubator for nuanced perspectives and ideas. Of the month-long event experience, Tsige says, “There were folks who had lived in that space and would tell history. There were other people in the neighborhood who would come through everyday. [It was] interesting to see how we were received in the neighborhood and so much hate (from rich white people). All the love was coming from the communities of color who have been there since forever.”

BUFU’s work also asks why many of those among the vanguard of our social, cultural, and political movements toward inter POC solidarity feel increasingly alienated and divided in the service of white supremacist modes and doc-trines or how, in the context of human to human interaction and the significance of it as a mechanism to getting free, people of color can engineer freedom via relationship construction. BUFU’s work doesn’t require that we do a better job of distancing our political or professional practices from our personal pathologies in the name of progression, but joining each other in the necessary endeavor of remembrance. Art as conjurer of ourselves.

Sonia reflects, “Growing up, I didn’t understand how racism affected my life and I had to educate myself to be able to relate to the term POC. At first I felt like that didn’t apply to me, but when I realized what racism meant to me I felt that it was really important…women who have been colonized unite.” Unfortunately, this spread in Posture may be BUFU’s last press feature for awhile. They explain, “Our interactions with press and other opportunities post and during our month in the warehouse have been a trip. For a lot of people, we fulfill a lot of diversity checkmarks and it isn’t always clear what gaps we are filling for them, or why they are interested in the work we’re doing — especially with white folks and institutions. On top of that, we have a lot of feelings about celebritism, commodification, and capitalism; navigating those contradictions within BUFU has to be strategic because we care about leveraging various platforms and opportunities to get this conversation and disburse resources to as many folks as possible.”

If you’d like to know more about their forthcoming work, a five-part documentary series slated for release in 2017 that Tsige describes as in its nascent stage and “cascading into this super weird, useful thing,” come down to the community where people are, because that’s where they’ll be. These live archiving spaces are intended to be the embodiment of community and conversation. The revolution is nigh.

WRITER’S NOTE: The following statement is dedicated to Jiun Kwon, co-founding member of BUFU, radically fierce femme and political activist who stood in solidarity with all oppressed peoples and devoted her life to ending police terror and brutality. This is also dedicated to Latasha Harlins and Akai Gurley and Soon Ja Du, who, like so many others, adopted anti-black racism as a means to survive.

“It’s almost been a year since Jiun’s passed away. Almost a year since we all got together and started our weekly meetings. We’ve made a lot happen in so little amount of time and I know she’s always been there in every step of the way. Wish you were here, 언니. It makes me so sad to think about it. I wonder what you would say with all the things that we’ve been through and all the things we’ve been working towards. I wish I had your patience and your tenacity. The things we’ve accomplished so far have truly been a life-changing experience for me and I feel like your spirit has been guiding and helping us in so many inexplicable cosmological ways. Whenever I think about you, I feel like I need to step back and really look at myself when I get lost in the endless work of the project. I wonder what you would say in times of adversity with your wisdom, and wish that you were there when we’d be chilling in the 찜질방 having fun drinking 식혜 or getting into all those clubs for free because Tsige & Jazmin’s are the homies for finessing. I miss you so much. You’ll always be in my heart!”

— Sonia, Tsige, Jazmin, and Katherine

For more information please visit bufubyusforus.com.

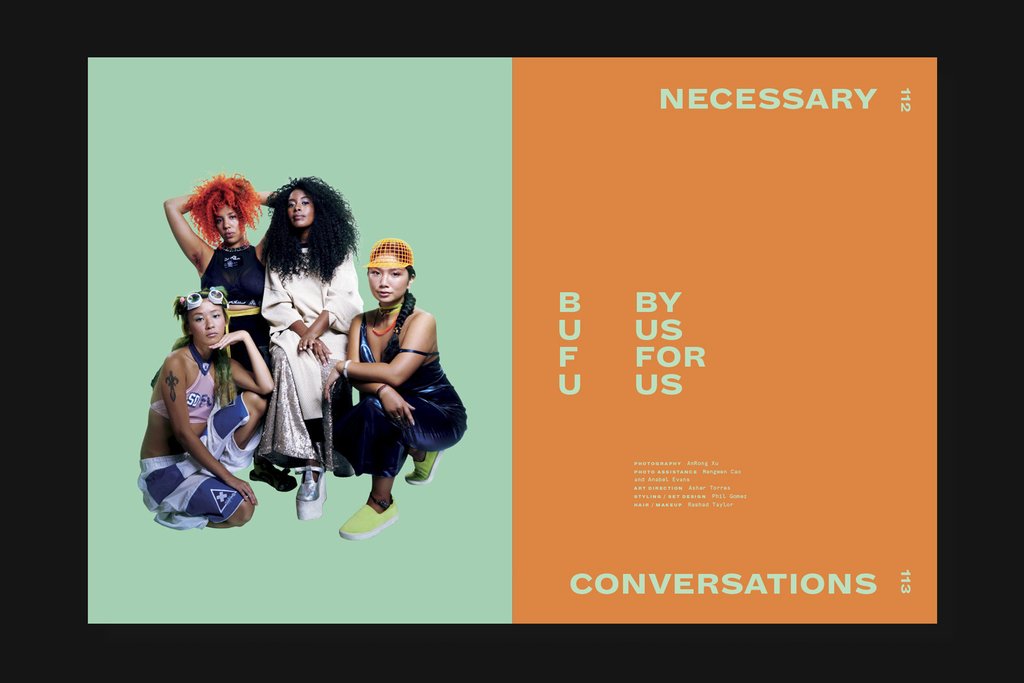

This special collaboration with photographer AnRong Xu, was produced as an original editorial and interview with BUFU for our third print issue.

Photography AnRong Xu

Art Direction Asher Torres

Styling and Set Design Phil Gomez

Hair/Makeup Rashad Taylor

Photo Assistance Mengwen Cao and Anabel Evans

Posture’s third print issue — The Boss Issue — is now available for purchase. This 168-page magazine features exclusive interviews with artists, theorists, activists, and nightlife icons. The conversations dive deep into ideas of leadership, success, and organizing in queer/trans/non-binary and WOC communities. This issue also represents a new design direction for Posture, one that reflects the mission and purpose of the publication.

Order your copy today through our online shop: shop.posturemag.com.