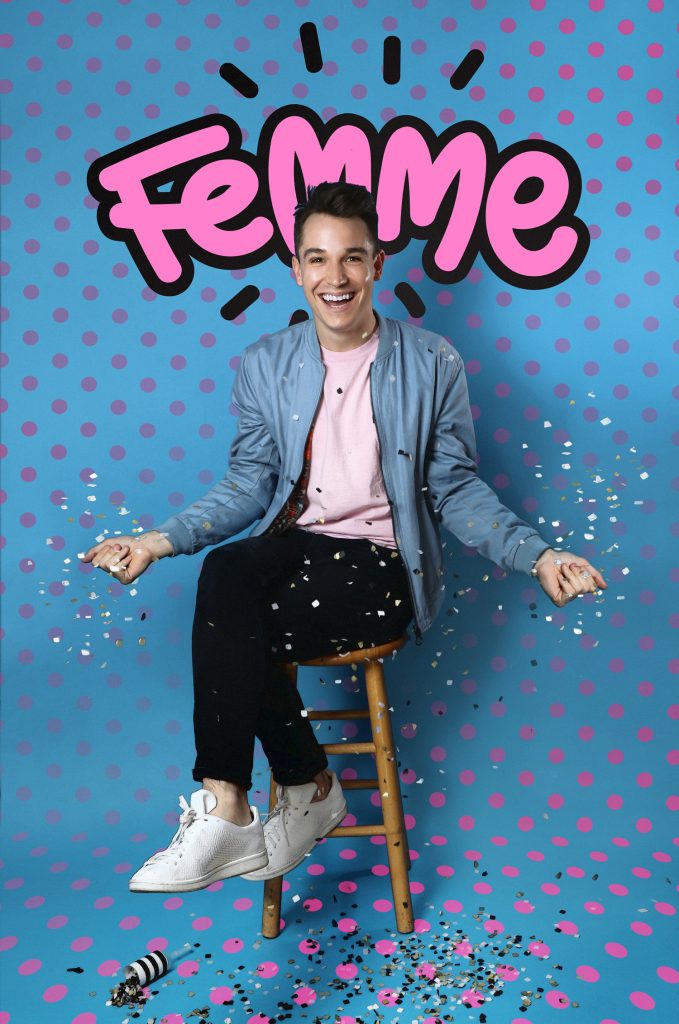

Corey Camperchioli is a lot like Carson, the main character of his new film, Femme: warm, exuberant, buoyant. He’s a hugger. But he also carries himself with the confidence that Carson has yet to find. When asked about the film, Corey answers with a thoughtful eloquence merited by its complex themes of gender performance, gender norms, and internalized misogyny. Then, just as quick as his character, he’s bouncing to the next sparkling bit of lightheartedness.

Femme follows Carson, a gay twenty-something who is rejected by a hookup for being “too femme.” The incident hurts — I cringed at the line, “If I wanted to date a girl, I’d be straight” — but it launches Carson on a journey of self-discovery, aided by his friend Harper (played by Stephanie Hsu) and a self-acceptance-preaching drag queen named Panzy La Rue (played by Aja of RuPaul’s Drag Race fame).

The short film’s story brings to mind a line from Alexander Chee’s essay Girl, in which Chee describes the first time he dressed in drag: “I have been trying to convince people for so long that I am a real boy, it is a relief to stop, to run in the other direction.” During our conversation, I read the passage to Corey and, with tears in his eyes, he said, “Yes. Yes. Yes.”

Femme launched on Kickstarter in February 2017, met its fundraising goal of $10,000 in just 28 hours, and went on to raise $25,453 over 30 days. The film premiered at Wicked Queer, the Boston LGBT Film Festival, in March and is now making the festival rounds; it’s been a selected by Frameline, Inside Out, Out Web Fest, FilmOut San Diego, and OUTShine, Outfest LA, among others.

Directed by Alden Peters and Executive Produced by Rachel Brosnahan, Femme has a dash of the magical realism of place that drew me into The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel; as Corey says, it’s New York where “anything can happen — and usually does.”

Corey wrote and starred in Femme and is currently adapting it to series between screenings. We met up in Brooklyn to talk about his creative process.

Photo by James Avance

The character of Carson is based on your own experience, but aspects of his character are fictionalized. How did you get inside his head?

I navigate the world as someone who people perceive to be femme. I knew Carson’s femmeness was going to be core to who he was, just like it’s core to who I am, but the thing is: it’s just my day-to-day. I don’t think about it all the time. Then there are moments when it just zaps you and you think, “Does everyone treat me differently because of the way I move through the world?” It’s like when you hear yourself on a voicemail and think, “Does my voice sound like that?” But you don’t think all the time about the way your hips sway. I wanted it to be something Carson doesn’t think about — until he does, and then he spirals out of control.

The incident — when Carson is turned away at the door — that, specifically, has never happened to me, but from a story perspective I was like, how can I raise the stakes right off the bat and drop you into this world? And that was the best way for me to heighten things. Because, honestly, just Grindr and online hookups are wild, truly insane. When you open the door to a stranger and you both have agreed to hook up, and your heart is about to jump out of your goddamn chest, you’re thinking, “Are they going to be a serial killer?”

When I’m at a screening of the film, the first scene is the hardest for me to sit through because the humor awkward, and I never know when people are going to laugh. It’s a crapshoot.

Tell me about your writing process.

I’m a writer because a writer is someone who writes, but I never thought that I would be a writer. I became a writer out of necessity, needing to have my voice heard.

The weekend is my time to write since I’m busy with work during the week. I like to have at least one day during the weekend where I don’t leave Astoria — it’s my “fill my cup back up” day. I like to pamper myself. That’s probably when I get the most writing done.

I’m super inspired by Frank O’Hara. He’s my number one. Just that day-to-day life can be poetry. The second I read Frank O’Hara, I was like, oh wow, my life is poetry, the fucking stop sign with graffiti written on it is poetry, the way that pigeon took a shit on someone’s head is poetry, it’s all poetry.

I dabbled in poetry in college and wrote a play right after I graduated called 3, which is about a couple navigating a threesome and they basically make a contract that states what they will and will not do. The whole play is them negotiating this contract. It had nothing to do with my life at all — I’d never been in a relationship, I’d never had a threesome, it was a straight couple. They were trapped in this 9-to-5 cycle and wanted to feel something again. And I didn’t have those life experiences at all, whereas Femme is essentially my life story.

What do you need to be able to write?

I try to stay away from this thing where “I need inspiration to strike me” in order to write, because, you know, she’s a fickle fairy. You never know when she’s going to show up, so I try to just sit down and crank it out.

What’s exciting for me is never knowing where my characters are going to take me. I try to enter every session just letting them do their thing. And I’m also someone who very much plays by the rules in life, I’m a rule follower, so I love thinking about that thing I would never do, and then have this character do it. Your instinct in life? Let them do the opposite. That is what I want.

I heard you were a fan of morning pages — writing a page of whatever comes to mind first thing each day.

I don’t think Femme would have happened if not for the morning pages. A lot of things in my life weren’t going well, or not as planned, I guess. On the acting front, I had a really sobering moment where I was like, if I keep on the path I am on, my dreams are not going to come true. Nothing was happening. I did a pilot out in LA with Benno [Rosenwald, the film’s producer]. After the pilot, Benno said, I want to work with you, I want to manage you as an actor. He told me this at this sushi place on the Upper West Side, and it completely changed my life because I had been with Benno at parties, I had been in drag around Benno, been kiki’ing with Benno. He knew who I was. Around industry people, I always felt like I had to act straight. Benno was like, I know who you are and your queerness is the best thing about you. It’s not something you need to stifle or dull down. I left that meeting hysterically crying because I had never felt seen in that way before.

Benno started managing me, but I kept hearing the same thing: you’re too specific, we don’t know what to do with you. So finally he said to me, you need to write something for yourself. If you write something for yourself, I will produce it. That gave me the permission to tell my story, which completely changed my life. I do think for so many queer people, you grow up thinking you shouldn’t take up space and you shouldn’t be yourself, and society tries to beat it out of you. So for someone to say, I want you tell your story, which is distinctly queer — that was a game changer.

Then came the next step: what is my story? Like I said, I didn’t see myself as a writer. I was becoming a writer out of necessity. And that’s where morning pages came in handy.

Every morning, these questions of gender norms and gender performance kept coming up, and I realized I didn’t love myself. Seeing daily in all the dating apps “no femmes,” walking into queer spaces and feeling that masculinity was prized. I felt like if I didn’t wear a backward hat or a tank top with my muscles bulging, I wouldn’t be accepted. And I was feeding into it. I was going to the gym, my body was shredded. But I was unhappy and didn’t feel worthy of love.

With morning pages, if you see the same thing showing up day after day after day, you get to a point where you have to do something with it. I found the themes of Femme there.

Once you found those themes, what was writing the script like?

It actually took a really long time to write it. I think it took a year to write seventeen pages. My biggest problem was that it wasn’t active enough. I had a lot of scenes with Carson and his friends just like, having brunch and talking about these issues. The feedback I was getting was show show show show. So we took that brunch scene and put it out into the gay club. I had this scene with Carson’s straight friend teaching him how to present straight, how to deepen his voice, how to walk manly. And that felt a little bit too Birdcage-y, so we took that scene and put it out on the street, and Carson grapples with that while doing his day job.

There were a lot of rewrites in that year. I have a folder on my computer just called Femme Drafts. There’s got to be… twenty? The good thing about shooting something is that it gets to the point where it’s like, okay this is it, we gotta send it to the actors and the crew. I could have picked it apart forever and I’m really glad I had a deadline there.

Honestly, though, that’s what kind of scares me about the prospect of moving this into a series: deadlines, but not having the luxury of time I had with the film.

Tell me about Femme the series.

We’ve had offers to go to series, but nothing has been decided just yet. Right now, I’m working on the pilot. I did a brainstorming session to outline it. I worked with a coach to do that, Kristin Hanggi. I initially approached it like I truly was a conduit, not knowing where it was going to go, just saying yes to everything that popped into my head. To all the writers out there: just say yes, say yes. It popped into your head for a reason.

From those ideas, we crafted an outline of the pilot and the season. We took all the different beats and put them on post-it notes and mapped it out. I put the map of post-its up on the door in my bedroom and I don’t actively look at it, I don’t spend time with it, but I glance at it while I’m getting dressed or hanging out. I find that once something’s marinated for a couple weeks, the second you decide to sit down and write, it’s all in you and it all comes spewing out in the most delicious way because your body’s really had a chance to process it.

With the short film, I had no idea what I was doing, so I just started writing. That was cool too, but where I am now, I need to be more diligent. I’m focused on a body of work, on the whole series. Still, I love those moments where you don’t have an outline and you’re just writing your character and when they go down this different path, you follow it. You’re chasing them, and they do whatever they want and you allow them. That’s the best feeling as a writer, to be surprised by your character.

In what other ways does writing the series differ from your approach to the film?

With the short, I had to kill a lot of my darlings, so what I’m most excited about with the series is being able to truly find out who these other people are. A short film just has to be laser-focused; there’s only room for it to be about one person. It has to be through their lens, and everyone else is about serving their journey. So the difficult thing for me was creating these other three-dimensional characters without being able to fully dive into their life stories. It’s all about these small moments that are indicative of who they are. Like with Harper, when her character sarcastically says, “You’re saying as a woman, I wouldn’t get how being feminine makes me lesser in the eyes of men. Yeah, I’ve never experienced that.” There, that’s what you need to know about her in the short, but that’s a whole episode later.

About that line. You said in an interview, “If a gay man is told he’s less than because he’s femme, what does that say about how we view women?” Do you consider the film a feminist film?

Absolutely, 100%. In the beginning, I was so focused on the issue of femmeness in the queer community and wanted to unpack that, but every time I came up for air, I was like, femme, femininity, female — this is half the population’s day-to-day life. So it was really important for me to draw those correlations and strengthen them and show how this is a problem for women every single day. At the same time, I’m very conscious that that’s not my story.

And that’s why Harper’s scene was so important for me to get right. The whole point of Femme is I want you to be laughing but I want you to be thinking as well, and it’s funny because that line where Harper checks Carson — in Boston, that was the biggest laugh in the whole film, but in Miami, no one laughed. It’s interesting to me the way that people encounter that line. Either they think it’s hilarious because it’s so true or they’re silent because they need to process how it’s true. But it was really important for me to know and show that this is an issue that goes far beyond just the queer community.

What are you favorite books? Who are your favorite writers? What else influenced the writing of Femme?

Frank O’Hara, my number one, through thick and thin. Growing up, I really loved The Perks of Being a Wallflower. It really reflected the hardships of growing up and feeling different. Me and my best friends, we had one copy of the book and we would pass it around and we each had a different color highlighter and would highlight the passages that meant the most to us. Just Kids, the memoir by Patti Smith, completely blew my mind, just the romance of New York City. I try to live my life in a way that will allow me to tell my grandchildren romantic stories about New York. I’ll be walking down the street and I’ll be like, I’ve got to put this in the memory bank because it’s one of those quintessential New York stories that I get off on.

Tell me one.

Well, this wasn’t New York, this was Miami. We were in this club, we leave at 2:30, we’re in Burger King, and I meet this beautiful man in line waiting for my chicken sandwich, and we just start kissing in line in the Burger King. That’s life, man. That was yesterday.

But it’s the kind of thing that happens in New York. Walking down the street, locking eyes with someone and feeling that electricity. I’m walking down Second Avenue and I see this guy, so beautiful. We walk past each other and I’m wearing this fake nose ring because I’m that girl, and suddenly we’re kissing in this alley, he just pushes me against the wall and we’re kissing. I think of Frank O’Hara as tied to that, this glorification of sexual experiences.

Stories about New York inspire me and that’s totally in Femme. I wanted to capture what it feels like to be a gay man in New York in 2018. I wanted to capture that feeling of walking into a bar and, depending on your mood, feeling like a troll or feeling like Gigi Hadid — there’s no in between. That’s maybe not Frank O’Hara’s New York, but that’s New York for me, for better or for worse. New York is a place where anything can happen — and usually does.

How important is it to have empathy for our characters? For instance, how did you approach the character of Evan, the guy who turns Carson away?

I don’t think that Evan is inherently a bad person. Evan is the product of a society that worships masculinity. When I think about the internalized homophobia and misogyny within the community, and why Evan would make those decisions, I think about how for so many queer people growing up, gender performance is tied to sexual orientation. People see feminine behaviors in a boy and think, he’s gay, when obviously we know these are two different entities.

People informed me that I was gay before I knew I was gay, because of the way I spoke and because of the way my hips swayed. Your natural inclination is to try to deepen your voice and try to assimilate — which, for me, didn’t last long because this is who I am through and through — but for a lot of people, they do dull it down. Then they go out into the dating scene and see these behaviors that, for their whole life, they have been told are wrong — so of course they are going to take it out on that person.

In the series, I’m excited to explore who Evan is in more detail. When he turns Carson away, that’s just one moment of his life. I can see things from his perspective; I did some femme-shaming in the past because I didn’t love myself. Even if nothing else happens with this movie, I have learned to love myself and that’s the biggest gift. It’s exciting to me to say I’m open to anything in this world — femme, masc, here for it.

You’ve been acting for a long time and you’re getting used to calling yourself a writer. For you, what’s the purpose of storytelling?

To feel seen. I personally wrote this story because I had never seen a femme character as the protagonist of a film, as the person right at the front. They were always secondary characters, the butt of the joke, someone who is not sexualized. For me, Femme means I am worthy, my story is worth telling, and I deserve to be at the center. I have had so many issues taking up space and apologized so much for who I am. Femme is a way for me to tell my story but also to validate the stories of other people.

So many people are reaching out to me and saying, “I’ve never seen my story in a movie like that before.” People get so emotional about this film because they’ve never seen themselves represented like this before. I think about the power that Benno gave to me when he gave me permission to tell my story. Part of what I want to do through #freeyourfemme is to encourage people to tell their own stories around femininity. It’s about telling my story and giving people the space to tell their story as well — and those two stories in dialogue is the story.

For more information please visit femmethefilm.com.