In a hetero-normative world, even things that first appear to operate outside of the limits of gender and sexuality, like technology, are often created within the traditional boundaries of sexual politics. Upon realizing technology was heteronormative, artist Zach Blas decided to propose alternative queer theories for the performance of technology.

“…in regards to programming languages, why not question why plugs are gendered male and female?”

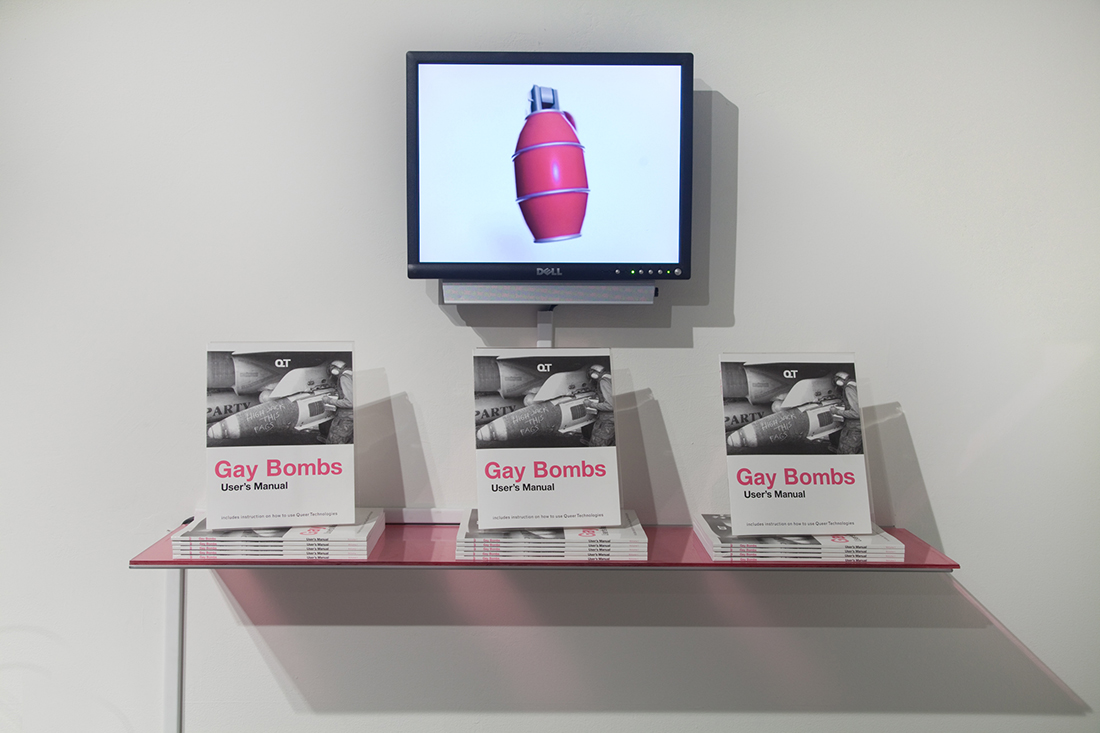

Blas constructed technologies such as the “Gay Bomb,” a technical manifesto which outlines what he defines as a “how to of queer networked activism.” Once he learned more about how the normative technological architectures and design platforms currently are, Blas, who has demonstrated the theoretical functionality of his work at Eyebeam Art + Technology Center in New York, created a gay anti-programming language he named, “Transcoder.” In reading about the ways even electrical plugs are based in gender politics, Blas created a queer solution that defies the male/female binary logic of gendered power adapters. In an era of Apple led innovation, these queer products are exhibited and deployed cheekily in an imaginative safe technological space, Blas calls, the “Disingenuous Bar.”

The groundbreaking conceptual artworks are known collectively as “Queer Technologies.” Blas’ disruptive works have earned him the 2010 Prixxx Arse Elektronika Golden Kleene from The Kenan Institute for Ethics. We caught up with the artist right before he left New York to teach art at Goldsmiths, University of London, to talk about how he creates alternative ways of being for technology.

How did you come up with the idea of Queer Technologies?

After I finished my studies in film, it already felt a little dated for me and my attention turned immediately to focusing on the media of our time. I just wanted to be much more engaged with urgent contemporary issues. At the time, film didn’t seem like the best place for that, so I started studying the histories of electronic media. I have always had a long-standing interest in queer politics. There was so little work done at the relative to thinking about queerness in relation to actual technology.

I’ve never questioned the way technologies are made in terms of gender.

Yeah, with technology or science, we often don’t question why things work the way they do. We just say things like, “Oh, that’s technology and that’s the way it works.” However, in regards to programming languages, why not question why plugs are gendered male and female? As I started studying technology, I discovered there were certain queer figures who were important in the history of digital computation. I wanted the work to be quite simple even though it’s an instinctively challenging thing for most people to dive into. So I used the allegory of plugs because the entire civilized world of people have an interaction with them on a daily basis. But, some people want to know why these plugs are labeled as male and female? And, perhaps even further, why do plugs connect through heterosexual intercourse?

So this project is about rebranding technology?

“Queer technologies” started as a massive design and branding project. It took actual examples of all these technologies and subverted them. In theory people could encounter the products and understand what they are seeing. And of course people encounter technology as something consumable. It was important for me to follow that logic and develop products.

How did you imagine the “Gay Bomb” technology to work?

When I was writing the gay bomb software manual I did a lot of research and what I came to discover was that there were two examples of “Gay Bombs” that you could identify. One would be a militarized version of the “Gay Bomb” that was an actual weapon the U.S. Air Force was developing in the 1990s. It was a bio-chemical weapon that would be deployed to turn enemy combatants gay. So it was pointedly this idea of gay shame. Enemy combats would become gay for each other and they would be so embarrassed that they would surrender. In 2003, there was a bomb dropped in Afghanistan that had graffiti written on its side that said, “Highjack this fag.” Then, there was this other side of the gay bomb that tapped into queer art, where you find bombs that represent the larger societal threats to queerness. So I took existing ideas of the “Gay Bomb,” and used them to create a queer manifesto.

How is the “Gay Bomb,” different than the “Transcoder?”

The “Transcoder” was really about thinking very precisely at the level of the programming language. With high level programming languages, there are a lot of gender dynamics that are actually a part of the way these languages are written. It’s one of those things where people claim that because programming languages are so technical that’s the way they have to be written. But actually no, programming language goes back to the post-World War II period when women were actually referred to as computers themselves. The point is, programming languages actually emerge from a highly gendered environment and you can see that logic creep in through the development of programming languages.

So did you envision “Transcoder” as a kind of software?

It’s actually a software developer’s kit that is neither finished nor fully developed. I offered a bunch of tools with the understanding that people would add to it and make it their own.

What’s also interesting is that Queer Technologies lives in the digital but also takes on physical space.

I’m one of those artists whose work is about something and I want people to understand that. One of the reasons for me creating the “Disingenuous Bar” display is because it is an easy way in. When you are supposedly holding a product you are going to ask questions like “how do I use this?” When encountering a work of art, you bring a different cultural lens to it. I wanted to move away from that and one way of doing that was creating the “Disingenuous Bar,” as a performative space.

What are you working on now?

I started this other project called “Contra-internet.” It’s about what we think of as the Internet today. We think of the Internet as a totality, and it is hard for us to imagine an alternative. The Internet has become this premiere place of control and surveillance because it is the place we go for digital networking. I want to break the idea that the Internet is the end point of digital networking and think about the alternative. I think it’s an interesting question for queer politics.

For more information please visit zachblas.info.

This feature was originally published in Posture’s second print edition, available for purchase via posturemag-shop.com.