“Alfred Hitchcock is usually placed outside noir. But at heart, no director is more deeply noir.” – Foster Hirsch

It’s summer of 1948. Hollywood was still in the “innocent era,” of the 1920s, 30, and 40s, feeling the pressure of the hays code to be “wholesome” and “moral.” It is the time of film noir, a stylistic theme with the mood of war and post war disillusionment. The suppressed stomach that was America needed an outlet to make sense of the new households that they came home to. The new complex dynamics between everyday men festered with the pang of moral ambivalence that was felt by all in the nation.

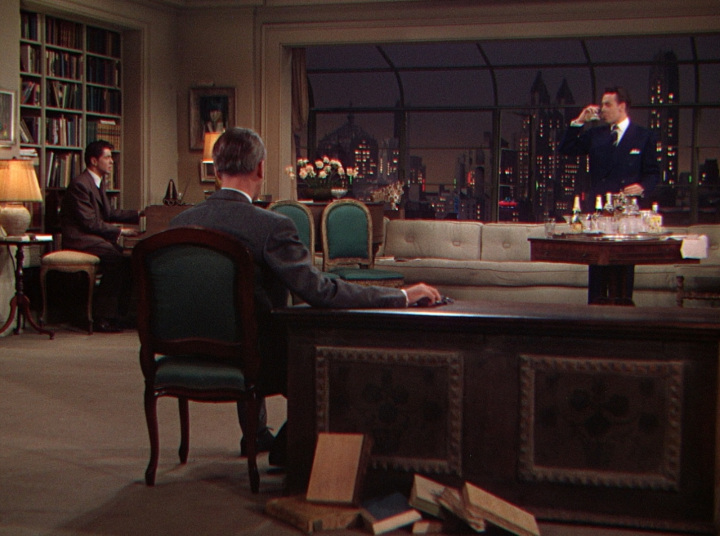

Alfred Hitchcock answers with perhaps the first murder mystery party and his 40th film: Rope. The entirety of the film takes place in one night, inside a Manhattan apartment, after two gents strangle their subordinate classmate, David Kently. Hosts Brandon and Phillip test the “perfection” of their murder by inviting close friends and family to a dinner party.

The plot does not so much relate to noir directly except for the sadonist implication of the killing. James Naremore in More Than Night insists, “Rope is a psychological film that can be linked to the noir series only because of its spellbinding sadism,” (19). The pleasure of the assassination plays out for Phillip and Brandon in their game to challenge their intellectual superiority with their carefully chosen list of invitees, including their formal schoolmaster, Rupert Cadell.

In Hitchcock’s interview with Francois Truffaut, Truffaut argues that the plot is not specifically important to Hitchcock, as he is only concerned with how the script is visually presented. So for the purposes of this his “single shot” technique, the specifics of the plot do not matter so much as the underlying connotation: homosexuality.

As noir is generally understood to be a style rather than a theme, it lends itself to the mode of visual connotation, as opposed to Westerns that are more in conviction of theme and therefore conveyed with denotation. Paul Schrader writes in his famous essay “Notes on Film Noir,” that noir is not a genre: “It is not defined, as are the western and gangster genres, by conventions of setting and conflict, but rather by the more subtle qualities of tone and mood. It is a film “noir,” as opposed to the possible variants of film grey or film off-white.”

The setting and conflict of the plot seem more obvious than they actually are. As the dinner party continues into the night, Brandon and Phillip boldly relinquish hints, as guests grow more and more suspicious. Conversations of David’s strange absence haunt Brandon and Philip. Brandon tries to conceal his anxiety, intoxicating himself. David’s aunt, who prides herself as being a psychic, reveals that he will be famous with his hands. Denotatively, this would only suggest his promising talent with the piano. Connotatively, this suggests her prediction to be telling of the consequences of his ill fate.

No more does the witty banter of the hardboiled tradition of noir relay subtleties as the stylistic qualities and methods. Hitchcock’s “single shot” and fade away technique create perhaps the cheekiest innuendo of them all. As most elements of noir were an unconscious, but beautiful byproduct of their budget limitations and compliance to puritan code, Rope was no exception unfolding from subconscious of Hitchcock.

The state of the art equipment of the time held only ten minutes worth of film, which was perhaps not coincidentally corresponded with Hitchcock’s use of montage. A sequence in Rope varies from nine to ten minutes, but from start to end, Hitchcock’s intention was for all shots to be ten minutes. Five sequences are actually filmed in a ten-minute takes. Though it is suggested that perhaps he blacked out the frame each time he turned over a new camera (Miller, 114).

D.A. Miller in his essay “Anal Rope” pinpoints how the transitions erotically reveal the homosexual relationship between Philip between David, but more importantly the hidden identity of the gay male. Ironically, and probably noticeable only upon the second viewing of the film, one might observe that many of the transitions in the film are made by the camera panning into the backside of a man’s suit. This is Hitchcock’s Freudian slip. Though it is never said, it is felt, the viewer enters a “noir” area. This is the invitation to wonder, according to the film, what is gay sex?:

Under cover of these blackouts, two things get ‘hidden.’ One is the popularity privileged site of gay male sex, the orifice whose sexual use general opinion considers (whatever happens to be the state of sexual practices among gay men and however it may very according to time and place) the least dispensable element in defining the true homosexual. The other is the cut, whose pure technicity a claim can hardly be sustained at so overwhelmingly hallucinatory a moment, even if the script didn’t link the word with the body wound of irreducible symbolic importance (Miller, 127).

This stylistically symbolic, and quite possibly unconscious troupe in Rope, is a key element of noir finding a way around the hays code to depict the anxiety of moral ambivalence. In this sense, Rope is the gaze of society into a mirror whose post war disillusioned reflection stares back at itself self-consciously, ambiguously under the veil of homophobia. Repressed in the shadows of the low-key lighting of noir, homosexuality could be insinuated and denied just as easily as it could be developed. In the mask of connotation, the existence of homosexuality is portrayed like a Hegelian dialect: where the possibility of homosexuality is opposed by the possibility heterosexuality and the mutual contradiction reconciles to a higher truth that only the viewer can discern.

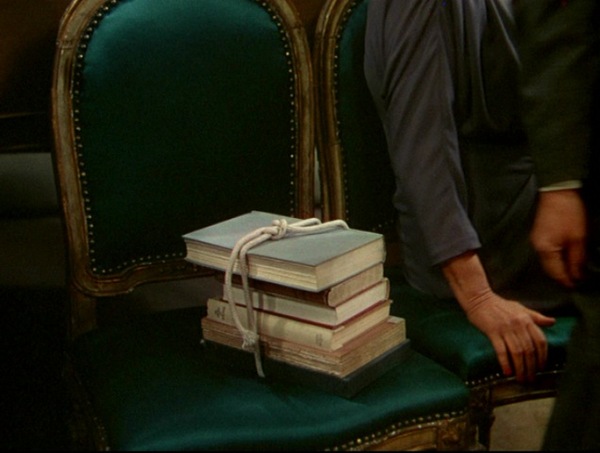

The existential ties to the under lying theme poetically hand us the ending of rope where the ending is unclear. Only the viewer can make up for himself what lies “in the closet.” David’s body rests in the chest at center stage, and is so to speak “the elephant in the room.” Throughout the whole film, the audience is teased with the voyeuristic prospect of looking into the cassone, and are left hot an bothered to the closing sequence where Hitchcock pans into a close-up of the appropriated coffin as you hear Brandon saying, “Go ahead and look. I hope you like what you see.” This is the accompanied unease and the paradox that is “the closet.”

In this case, connotation is the result of a cyclical ambivalence of gay culture. The encoded nature of subtlety allows for homophobia to occur. Connotation comes with the desire to reveal the truth, and the paradox is that there isn’t one. The desire is never satisfied and becomes the ghost that is homophobia. D. A. Miller argues that “Every discourse that speaks, every representation that shows homosexuality by connotative means alone will thus be implicitly haunted by he phantasm of the thing itself, not just in the form of the name but also, more basically, as what the name conjures up: the spectacle of “gay sex” (Miller, 123).

Like all other noir, Rope deals with the underlying anxiety of men, particularly the everyday man that is burdened with his godlessness, his fallibility that sentences him to his doomed fate. Noir is a style, a cubist painting, whose brush strokes attempt to solve the problems of men. Like all noir directors, Hitchcock works out moral conflicts visually rather than thematically, and because of the self-conscious nature of its identity the solutions to sociological problems are purely artistic. Paul Schrader points towards the tragically beautiful stylistic elements that make noir true to the anxiety of existence in the harrowing attitude of post WWII cynicism:

Toward the end film noir was engaged in a life-and-death struggle with the materials it reflected; it tried to make America accept a moral vision of life based on style. That very contradiction— promoting style in a culture which valued themes—forced film noir into artistically invigorating twists and turns. Film noir attacked and interpreted its sociological conditions, and, by the close of the noir period, created a new artistic world which went beyond a simple sociological reflection, a nightmarish world of American mannerism which was by far more a creation than a reflection (Schrader, “Notes on Noir”).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hirsch, Foster. Detours and lost highways: a map of neo-noir. [1st Limelight ed. New York: Limelight Editions, 1999. Print.

Miller, D.A.. “Anal Rope.” Representations 32 (1990): 114-131. JSTOR. Web. 19 June 2013.

Naremore, James. More than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts. Berkeley: University of California, 2008. Print.

Schrader, Paul. “Notes on Film Noir.” Film Noir Reader. Limelight Editions, 2009. 52-63. Print.

Please support Posture by choosing to become a member for only $45/year and receive benefits including our 168-page annual print magazine, VIP access to events, personal updates, and more. Please visit shop.posturemag.com for more information.