Author | Annie Malamet | Visual Arts Editor

Annie Malamet: Can you talk a little bit more about your new experimental play, brother lovers?

Zavé Martohardjono: brother lovers is a play that is the culmination of research, script writing, and performance experimentations I’ve been doing for the past 3 years. It features two characters from the the Mahabharata (a hindu epic that informs traditional Indonesian mythology): Karna and Arjuna. In brother lovers, I re-imagine these archetypes as two men who meet at a disco club and, not knowing they are brothers, fall in love and fall into an intense and emotionally fraught relationship that can’t extricate itself from the war and political conflict that surround and implicate the two brothers in different ways.

As an Indonesian, I grew up with the stories of the Mahabharata and I love the dance and wayang kulit (shadow puppet) performances of these stories. I started reading translations of the Mahabharata when I was in an emerging artists program at the hemispheric institute for performance and politics and for the last three years have been working out several performance “studies” of my own retelling and re-imagination of the relationship between Karna and Arjuna.

brother lovers also comes out of personal storytelling. I use the epic grandeur of mythology, big stories of state conflict, warrior stories to frame tender personal experiences. At root, brother lovers explores queer intimacy and love as both an important refuge, a space that holds true possibility of creating family, but also site for working out our biggest dysfunctions and challenges. Sometimes I jokingly describe brother lovers as simply a piece about the biggest, most dysfunctional relationships I’ve been in that just take years to understand and recover from.

[The play] is experimental in that it retells and kind of gives a twist on the original epic both by queering the story, but also by disrupting the framework of theater. Performers play multiple characters and I perform in the piece both as a Narrator and as guiding characters in the piece.

AM: How do you see your video, performance, and theater work interacting with each other?

ZM: I work in a lot of different mediums: performance, video, installation, writing. One thing both about my work generally is that it offers alternate versions of reality and hybrid space, myth space, dream space and collaged narrative to bring multiple experiences together. Combining multiple mediums helps me achieve this. I’m always thinking about things visually and as a filmmaker and video artist as equally as I think about what is emotionally compelling as a performer or director. Because the original mythology is so visually lush, I wanted to create a universe inside which this story exists. I use video to create either scenery that frame the performers on stage, or to set the scene with dreamy looking video that visually tells the brothers’ stories, or sets the emotional tone. I love the interplay of live performance with projected visuals. I think it adds a whole other dimension to creating a world.

In terms of performance, this is the first piece I’ve written and directed that draws so traditionally on theater. Usually my work falls more into the performance art category. What’s nice about theater is that you can go so deep emotionally to tell a story. It’s been wonderful directing my cast and watching them explore their characters so beautifully.

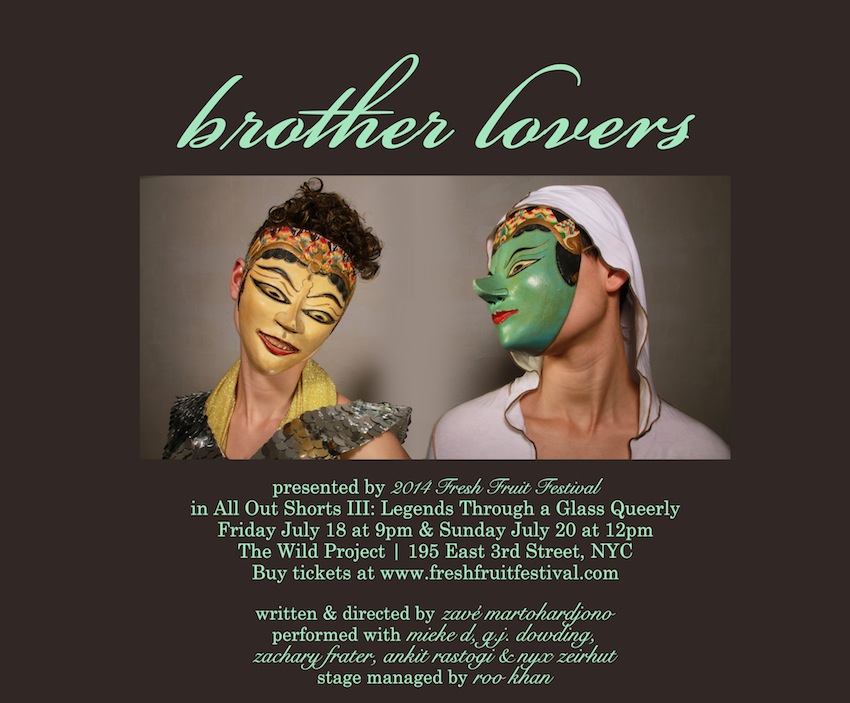

I also work with colorful masks that I make, and costumes, that mirror the grandeur of the mythology. It’s also a way to have different performers carry the larger-than-life stories. In this piece four of my cast have varying gender and ethnic identities but all play two brothers. My intention is to have a diverse cast carry this culturally specific mythology in a way that opens it up to audiences and opens up the possibility of relating to these ancient characters.

AM: Your performances are very movement oriented. How does dance and choreography shape the narratives you create?

ZM: I like to explore ideas artistically both through writing and through movement. Movement practice has been a very productive way to understand what I want to make work about and how I want to make it.

Dance and movement have recently become the primary way I find out what stories I want to tell. I’m moving away from heady brainstorming and more towards embodying and moving through ideas. Butoh practices feature a lot in my work because it’s this transformative, incredible practice for human bodies to throw away their limits and habits and discover alternate embodiments and temporality. Butoh has become an incredible form for me to explore ideas and expressions of in-between physical states, and creates space for me to address certain topics I’m interested in as a mixed-race, queer and trans* artist, namely questions around ancestry, otherness, and “authentic” identity. In my work, I approach notions of belonging, origin, and “home,” as fractured concepts. My practice manifests “between-ness” as a permanent state, not a state lacking wholeness or solidity.

Dance and movement have recently become the primary way I find out what stories I want to tell. I’m moving away from heady brainstorming and more towards embodying and moving through ideas. Butoh practices feature a lot in my work because it’s this transformative, incredible practice for human bodies to throw away their limits and habits and discover alternate embodiments and temporality. Butoh has become an incredible form for me to explore ideas and expressions of in-between physical states, and creates space for me to address certain topics I’m interested in as a mixed-race, queer and trans* artist, namely questions around ancestry, otherness, and “authentic” identity. In my work, I approach notions of belonging, origin, and “home,” as fractured concepts. My practice manifests “between-ness” as a permanent state, not a state lacking wholeness or solidity.

I knew dance would be important to brother lovers because traditional dance and even the movement of the wayang puppets is the way these stories are told. Dance is also so central to gay/queer culture, so I approached movement from different influences–Balinese and Javanese dance, gay club music and house and ball choreography, and then also meditation movement and butoh.

AM: I see the modes of representation you work within as essential to the de-colonization of the way we view art. Do you agree and if so can you speak to this?

ZM: Absolutely. Part of my practice and conceptual approach whether in video pieces or performance is to offer perspectives and voices that while perhaps considered “marginal”, are more often than not, widely shared. so, when I approach for example trans-ness in my work or speak to my experience of living in the “borderland” as a mixed race person, I speak or have characters speak from a place not of being marginalized, but actually more often from what I consider the ancient–a time before colonization when multiplicity and fluidity were not considered strange nor threatening. A pre-Western, pre-colonial time when there were more possibilities. And often my work is really the imagination of this pre-colonial space or reality, and it becomes a playspace for re-imagining or imaging everything differently–and subverting our internalized colonialism.

But on another note, because my work mixes so many cultural references (ancient Hindu mythology, house and ball references, disco, western and non western mask work, butoh), I see it as complicating colonial notions of cultural exchange. Rather than a power-dynamic-driven cultural appropriation or colonial consumption, I regard mixing all these various cultural influences (that have made their way into my mixed-race, queer life) as representing cultural exchange. Sometimes I consider my work like a complicated cultural drag. For example, what is my relationship as an Asian and white person to learning, practicing, and incorporating traditional Asian dance–even of countries I’m not from like Japanese butoh? it’s not a clear cut situation. It’s as much mine as it is not mine. I’m interested in the discovery of this exchange, not the consumption of these symbols and their meaning. Also, I think these references all have a lot to say to each other and when mixed together, there’s a beautiful collaboration that happens.

AM: What about non-linear narratives informs the vulnerability and deconstruction of identity you say you’re interested in working with?

ZM: Non-linear narrative features prominently in my work–whether in performance or in the films I’ve made over the years. Breaking narrative structures allows for the presence of unexpected voices and perspectives and gives space to speaking to experiences that are hard to delineate. This can mean identity experiences that are hard to categorize in finite terms. I love poetic non-linear narration. I love describing dreams as a way of storytelling. it’s about talking about ourselves and our lives from a raw and vulnerable place, from those visceral parts of our lives that don’t fit into what and who we are expected to be. Identity markers can be so limited–you have to pile so many terms on and even with a long list, I feel it never actually describes our experiences. With narrative, I try to cultivate intimacy between performer and audience, and I also sometimes turn to abstraction, collaging, and non-linear forms so that there’s surprise, intimacy, and layering, and so that the audience gets a lot more than we are all expected to get. i find it interesting that so much of my work is personal story-telling and culturally specific, and audiences often tell me they deeply identify with these stories and see themselves reflected. I think i use deconstruction and vulnerability to allow us to both have our very specific experiences that we are representing and also share so much commonality in listening to and understanding those experiences.

You can now buy tickets for brother lovers at The Wild Project, 195 East 3rd Street NYC, Friday July 18 at 9pm & Sunday July 20 at 12pm.