Author | Saby Reyes-Kulkarni

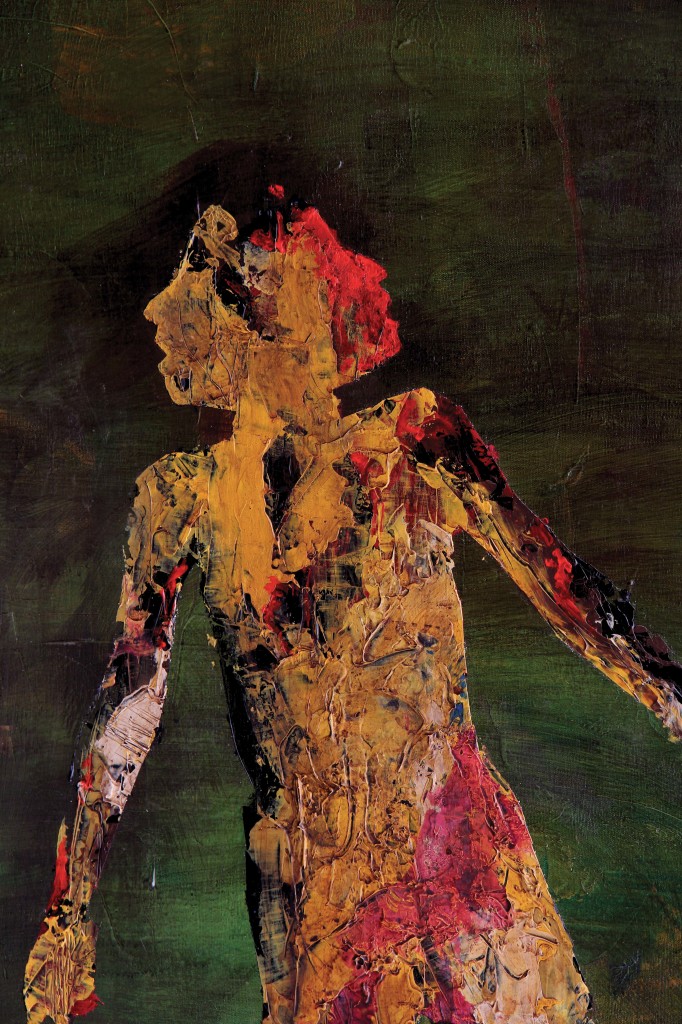

Though none of the songs on the new album Stranger by Bay Area grindcore outfit Cretin explicitly address the life experiences of the band’s transgender frontwoman Marissa Martinez-Hoadley, parallels abound in the music’s recurring explorations of identity, duality, and inner/outer conflict. Ditto for the album’s artwork: in a daring, almost reverse-subversive move for an extreme metal act, the physical release lavishly showcases nine fine art pieces by painter Emerson Murray, a friend of the band’s since grade school.

Murray had recently begun venturing into abstract representations of the human form in a new series of paintings when Cretin’s bassist and principal lyricist Matt Widener started coming over to Murray’s home to discuss the richly composed storylines he was preparing for what would become Stranger. Murray and Widener (who holds an MFA in creative writing and studied under Booker Prize-winning author James Kelman) immediately spotted potential for reflections between the two bodies of work. After a while, it only made sense to present them together as cover art.

“I think Matt suggested it, but I thought it was a stupid idea,” Murray chuckles over a Skype session as both he and Widener prepare for a group Star Wars role-play session. “Because I thought: ‘Your bandmembers and label are not gonna go for it.’ But some of Matt’s ideas were so visceral and brought such strong images to mind that I said, ‘You know, I’m not even sure you’ve convinced me that my work is right for your album, but I’m going to use some of your lyrics and just do a painting.'”

In turn, Widener took some cues from Murray as well.

“Emerson and I talk about the stuff we’re into,” adds Widener as Murray laughs in agreement. “We’re each other’s sounding boards for our art, music, writing, and all the things we like — books, movies… everything. It’s been that way for twenty years now. And even if there isn’t a specific mission or a project per se, we just end up involved in each other’s processes.”

Much to Murray’s surprise, both band and label — iconic underground metal imprint Relapse (a stable which at various points has included Mastodon, the Dillinger Escape Plan, Brutal Truth, Today Is The Day, Fuck The Facts, Pig Destroyer, etc.) — responded with enthusiasm. Listeners will likely do the same. In all of the pieces, featureless, ambiguously-defined humanoid figures occupy the foreground while contrasting background color schemes imply a tension between resistance and integration of the self against external space.

For this series, Murray — who has a background in cinematography and photography — would hire a model, photograph the model extensively in a series of poses, and then select the keeper image that he thought would translate best for the composition he was looking to get across on canvas. He would then paint an abstract image over the whole canvas before chalking-in an outline of a human figure based on the photo he’d selected. At that point, he would apply masking tape over the outline, paint a new pattern within the bounds of the masking tape and then remove the tape — a technique known as masking.

“I’d been thinking about using masking in my paintings for a while,” Murray explains. “Before I started this series, I’d been doing these cartoon comic strip word-bubble ripoff paintings. I was also doing some movie-still paintings, but I was searching for a new approach. I really like abstract painting, but I don’t think I have the courage to be an abstract painter. I like the body too much. So I thought, ‘Well, I’ll just do an abstract painting and do another abstract painting on top of it in the shape of a person.”

Murray came across a movie poster by artist Mark Simpson, AKA Jock, that Simpson had been commissioned to do by the Mondo t-shirt and poster company for a theatrical screening of John Carpenter’s 1982 horror classic The Thing.

“I saw that image and something clicked,” says Murray.

Even when Murray essentially limits his palette to two colors — “We Live in a Cave,” for example, which accompanies a song with the same title — the riotous color relationships burst with life and convey an intensity of mood, though they don’t clearly define what those moods are. Murray and Widener both point out that “We Live in a Cave” conveys celebratory overtones, but in an open-ended way that works, even in juxtaposition, with the tone of the song. Paired with the forceful impression that the paintings make, their ambiguity lends itself to being inhabited by Widener’s horrific narratives. They also provide visual and tactile expression for the ferocious sensory overload brought on by the music.

In the classic sense, Murray’s artwork acts as the vehicle for “the world” that an album pulls you into when it moves and connects with you. When vinyl and cds each had their heyday as music’s dominant media, it was customary to just sit and stare at the artwork and liner notes as you listened in an attempt to project your imagination into the music. But Murray’s cover image (also titled “Stranger”) works equally well as a transportive vehicle on digital platforms like Soundcloud and Bandcamp — proof, perhaps, that we as a culture haven’t lost our ability to properly augment recorded music with visuals after all.

Widener explains that his lyrics on Stranger illustrate various permutations of “the other.” As such he is especially fond of the back-cover image, a blue silhouette against a gold and black background entitled “Stalker.” More so than the other pieces, “Stalker” immediately communicates shades of menace and intrusion that play on primal fear instincts and arguably tap into deeply embedded body-language archetypes. The scarecrow-like figure in “Stalker” emanates harmful intent, its head tilted in an untamed swirl of blue that suggests psychic turmoil and the threat of violence — an especially fertile connection to the music considering that several of Widener’s protagonists are being intruded upon from within by their own compulsive desires, sexual or otherwise.

On Cretin’s full-length 2006 debut Freakery, Widener and Martinez-Hoadley reveled in fetishizing sexual depravity. Their lyrics at the time were rife with sensationalized depictions of sex acts that, to put it mildly, cross into non-consensual areas with myriad references to dominance, control, abuse, incest, abduction, assault, sexual assault, sexual assault by electrocution, coprophilia, and extreme body modification. At the same time, it was impossible to deny the satirical edge through which Widener and Martinez-Hoadley portrayed these scenarios.

Looking back now, Martinez-Hoadley flat-out admits that the words she penned for songs “Daddy’s Little Girl” and “Object of Utility” reflected fantasies she had long harbored prior to taking the initial steps towards her transition in 2007 (a process that would, understandably, put the band on hiatus until 2011). Both songs pivot a dominant male figure in relation to a captive sexualized object. On “Daddy’s Little Girl,” a father forces his cis male-born child to “model Mommy’s clothes / learn to strut and pose” and to “tuck his stuff back between his crack” — even going so far as to slip hormones into the boy’s food. Martinez-Hoadley inverts the dynamic somewhat on “Object of Utility,” where a character submits to being racked and bound as a piece of furniture, sheathed in latex from head to toe, and — ultimately — to having her lips, teeth, eyes, and arms surgically removed.

“‘Object of Utility’ was a sexual fantasy in my head at the time,” Martinez-Hoadley explains over a separate Skype session in which Widener also takes part. She points out that in this fantasy she identified with the female “object” character and stresses that the character is “completely compliant.” She starts to say “I didn’t tell anyone” before Widener cuts in.

“Yeah you did,” he says. “You told me!”

“Oh, I did?” she answers, laughing. “I tell Matt everything.”

Over these two conversations with Martinez-Hoadley, Widener, and Murray, it becomes abundantly clear that friendship not only holds Cretin together but acts as the central driving catalyst for the band’s creative process. Martinez-Hoadley and Widener go on to discuss how the new album reflects their expanded worldview — no surprise really, given that it was made eight years after the last one and in the wake of a major life change, not to mention Widener’s growth as a writer.

Over these two conversations with Martinez-Hoadley, Widener, and Murray, it becomes abundantly clear that friendship is the driving catalyst for this band’s creative process. Martinez-Hoadley and Widener go on to discuss how the new album reflects their expanded worldview — no surprise really, given that it was made eight years after the last one and in the wake of a major life change, not to mention Widener’s growth as a writer.

Mostly written in prose form as “flash fiction,” the new material surpasses the wit-laced wordplay and gallows humor that Cretin relied on in order to recreate the nostalgic, first-love vibe that Martinez-Hoadley, Widener, and drummer Col Jones felt more than two decades ago as teenagers headbanging to seminal gross-out death metal/grindcore touchstones like Repulsion’s Horrified and Carcass’s Symphonies of Sickness. This time around, Widener achieves genuine pathos as his protagonists grapple with various threats that refuse to be ignored and lunge forward demanding final resolution — often with gruesome consequences, but always rendered in a humane light.

Because some of these threats represent mirror-image or photonegative projections of the self, Widener underscores the music with a tone of existential crisis that lingers far more uncomfortably than the prurient shock he and Martinez-Hoadley favored in the past. Meanwhile, Murray’s artwork simultaneously frames, serves, enhances, and even adds a physical dimensionality to the quantum leaps that Stranger demonstrates. In essence, Murray has fleshed-out a synergistic parallel universe in the tradition of venerable cover-art design firms like Hipgnosis.

“It’s funny,” offers Widener. “With the piece that goes with ‘The Beast and the Drowning Bucket,’ the inside of beast looks like a star field. It almost feels transcendent. I get the same feeling as I do with the star baby at the end of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. It’s like, ‘Oh shit, someone’s figured out how to evolve.'”