The Brazilian native & MTV alum opens up about 80’s nostalgia, Western culture, female sexuality & industry representation, and CALIFORNÍA’s girlhood coming-of-age saga during the film’s Tribeca premiere last month.

We open to the interior of a young teenager’s bedroom: that of 15 year-old Estela (newcomer Clara Gallo), who we first meet as she begins her inauguration into the tumultuous throes of womanhood. Arguably the most sacred form of refuge for any adolescent, Estela’s bedroom is no exception: the unique intimacy evoked by her room’s distinctive interior suggests that this self-expressive haven brings young Teca a much needed sense of stability and comforting familiarity during what is an otherwise thrilling yet daunting time in her life. As the camera slowly pans around, we glimpse Estela sprawled in bed while her voice narrates the contents of a letter she is currently writing to her beloved uncle, a music journalist living in California whom Teca wholly idolizes. Director Marina Person invites us to peruse this space and probe every nook and cranny; and the period details that litter each frame—including the letter’s specific cultural references—suggest that we are in the early 1980’s. The year is 1984 to be exact, and with a faithful specificity to each decade-defining stylistic touch, Person crafts this scene in a manner that effectively establishes the film’s atmospheric tone, and fully immerses us in its sense of time and place.

Within minutes, the complicit voyeurism of Person’s camerawork and rich visual exposition offers deep insight into the various shades and dimensions of Estela’s identity. Observed with a gentle curiosity made intimate by Person’s idiosyncratic eye, the contents of Estela’s room—and the private moments, banal interactions, and conversations with trusted confidantes we ultimately find ourselves privy to—reveal the rich tapestry of her character. We notice, for instance, how Estela’s taste in décor parallels her spunky femininity, and projects the extent to which her love of Western culture influences her style [indeed, with her jet-black bob effortlessly tussled and flipped to the side, Gallo seems to be channeling a Latin Molly Ringwald], as well as her aspirations and interests—right down to the posters of sunny California that furnish Teca’s walls; visually projecting her West Coast wanderlust, in the footsteps of her uncle. (Fortunately, after having sacrificed her 15th birthday party in exchange for a trip to California once she turns 17—and with her 17th birthday looming just around the corner—Teca is now closer than ever to making this dream a reality—and when she’s not distracted by the foibles of young love, our protagonist’s anticipation is so consuming that we too nearly taste her anxious excitement as well).

Other objects and ornaments further abound with rich character clues; as the assortment of vinyl records and album posters shed meaningful light on Estela’s zealous love of music—we see a particular fondness for glam rock, British beat, David Bowie and Pink Floyd—and the recurrence of these visual cues, in conjunction with the ways in which Estela frequently turns to music as a way to connect with others, further reiterate music’s instrumental value (pun intended) to Teca. Yet Person also goes to great stylistic lengths to ensure that music’s exceptionalism isn’t just confined to the singular joy it brings Estela within California’s narrative. In fact, the film itself also seems to holistically benefit from having music baked into its very DNA; for Person’s eclectic and electrifying soundtrack—an indulgent nostalgic treat whose tracks include The Cure, Joy Division, Bowie, Echo and the Bunnymen, and many others—creates the film’s ambience and adds a meta dimension that quite literally speaks volumes of music’s integral presence within California’s overall aesthetic. Even Teca’s stuffed animals—perhaps one of the few remaining vestiges of her innocence—symbolize a wide-eyed youth that still endear her to childhood.

From witnessing Estela getting her first period at the film’s outset to eventually charting her first sexual encounter, California chronicles the whirlwind of milestones—both familiar and specific—that signify our central character’s impending womanhood. This coming of age tale is therefore not unlike many girlhood sagas of recent years which aim to capture their young protagonists’ confusing, exhilarating and often jarring foray into adulthood (from the superb Mustang and Girlhood; to Diary of a Teenage Girl and Blue is the Warmest Color; the genre seems to be experiencing an exceptional renaissance)—and as Estela learns to embrace her newfound desires and burgeoning sexuality, she too must navigate the insecurities, pressures, complications, and burdensome responsibilities invited by her blossoming adulthood. Like many of these contemporaries, Estela’s coming of age tale avoids finger-wagging indignation or judgment. What distinguishes this film, then, isn’t necessarily the nuance, humanity or respectful empathy Person brings to her heroine’s arc, but the rather unsentimental manner in which that very arc is tested following the sudden and unexpected news of a family member’s AIDS diagnosis—and the ways in which Estela must cope with this tragic and painful reality, while also grappling with romantic heartbreak and the palpable disappointment of her derailed dream trip, reveal a quiet humility and imperfect yet noble strength of character that speaks to a larger universal understanding of what it means to be an adult, and how personal growth and maturity often requires resilience in the face of struggle and despair. How fitting, then, to have this struggle be mirrored and distilled through the turbulent political climate that backdrops the film; for the decade saw none more despairing, universal or culturally defining than the widespread devastation brought by the nascent AIDS epidemic.

***

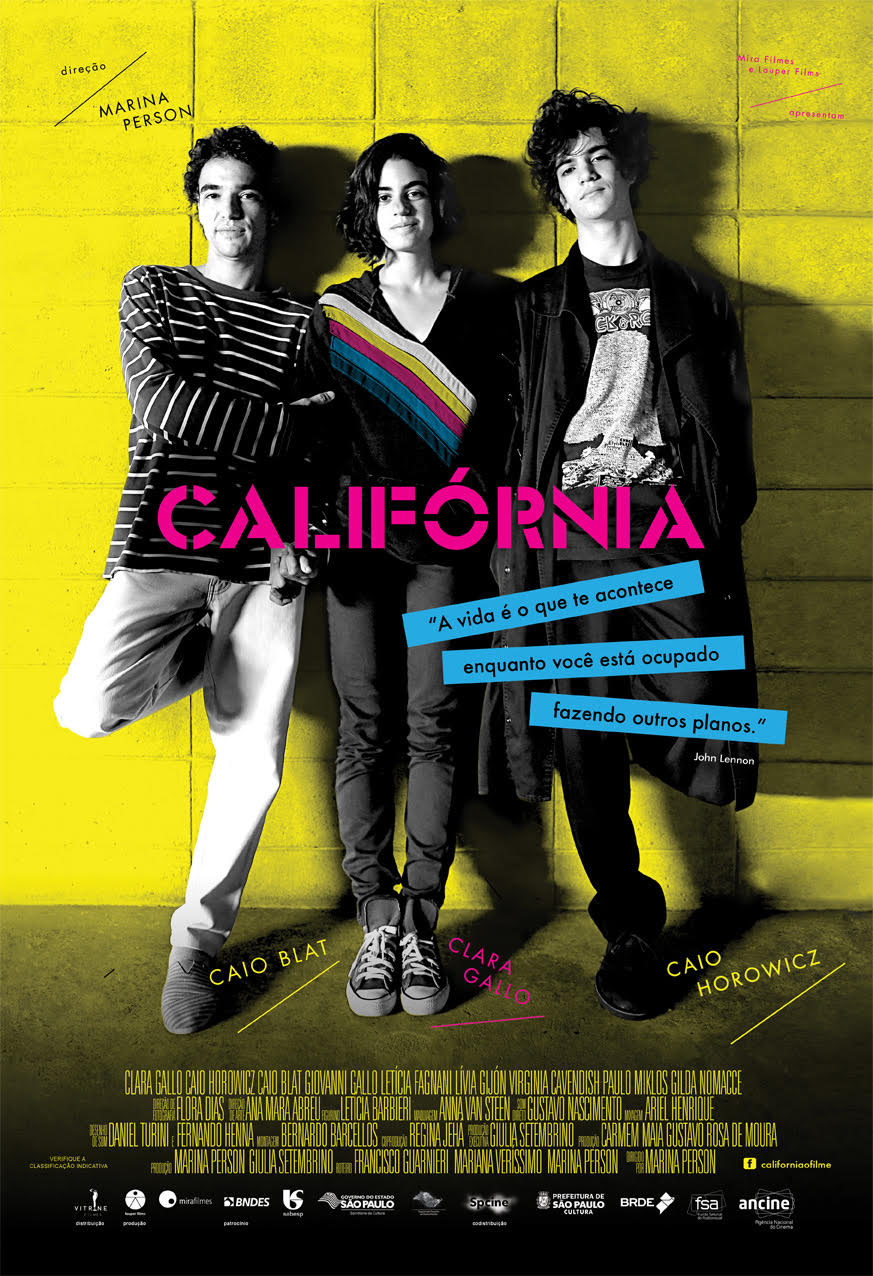

I had the chance to sit down with Person during last month’s Tribeca festival, where California made its North American premiere. A Brazilian native whose resume also boasts the title of actress, writer, and TV show host, Person is no stranger to the festival circuit. After winning Best Director at the Gramado and RioCine Film Festivals for the 1996 short “Almoco Executivo” she co-directed with Jorge Espirito-Santo, her first solo project and feature debut came with the 2007 documentary “Person”; a personal opus of sorts that went on to show at Locarno and Trieste. As with that film, CALIFORNIA is impressively buoyed by the infusion of its helmer’s personal experiences; which work to generously inform both Estela’s story and the film’s stylistic sensibilities. Because the film’s aesthetic palette is in many ways a love letter to the throwback music videos of yesteryear, it comes as little surprise that Person has 18 years of experience at MTV Brasil under her belt. Given the film’s autobiographical threads, I was eager to pick Person’s brain on her creative process and artistic influences; Brazil’s complicated political history and its charged social landscape in the 80s, which saw the country’s first democratic presidential elections following 20 years of military dictatorship; how this state of affairs further impacted her adolescence amidst the height of the AIDS crisis; and how the film’s examined juxtaposition between character (inner) and cultural (exterior) turmoil becomes a rich thematic allegory for the intersection between our personal and political experiences, histories and identities.

What follows is a slightly modified version of our conversation, edited for clarity.

How did this film come about as a project?

My first inspiration for this film was my own memories of being a teenager in Brazil in the 1980s. Politically speaking, it was a very special time—we had lived during a very tough period in our history, and after 20 years of life under military rule people were taking to the streets to encourage everyone to vote because we wanted our democracy back.

Mine was also the first generation to start having sex alongside the onset of AIDS—which is ironic because as the sons and daughters of the sexual revolution, hippie culture, and even the pill, our early sexual experiences were largely informed by the cultural liberation of the 60s and 70s—yet suddenly we found ourselves having to face this unknown and very violent disease that was connected to sex. But the film is not about AIDS or politics, it’s about this young girl—so I wanted to talk about how these issues affected Estela by showing these different experiences from her perspective.

Framing the AIDS crisis and its social implications in the background also allowed for an impressive navigation between fact and fiction—where despite the conventions of this genre dictating a certain adherence to historical record, unlike biopics, there’s a considerable creative leeway afforded—and you used that dramatic agency to achieve a stealthy balance between politics and personal experience through Estela’s story. I found this recurring dichotomy—collective vs. individual histories, shared vs. personal memories—to be most effectively rendered through your recollections of how the epidemic (and its heightened stigma on the gay community) fundamentally shaped your generation’s formative sexual understanding; as well as how the global attitude surrounding sex particularly impacted the sexual ethos of Brazilian culture throughout the decade.

Yes, exactly because in one way or another, these were issues that affected my youth, my own adolescence—and I wanted to talk about it from a female point-of-view. How is it for a girl to not be a kid anymore? [Estela] is a teenager when she gets her first period, and a lot happens between that moment and her first love, her first sexual experience. You know, there’s a lot of internal dialogue when one loses their virginity: so it was important to convey what’s going on in Estela’s head, the things that can happen, the plans that don’t necessarily go as expected.

Similarly, the upcoming democratic presidential elections mentioned in the film were a watershed moment in Brazilian politics—so in many ways, this is a film of firsts.

It is, it is. But it’s also a film about—I mean, the title itself is California; a place Estela dreams of and has concrete plans of going to. You know the quote “Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans”? This is what the film is essentially about: things in life may not go according to plan, but sometimes other things unexpectedly happen that are just as beautiful as what you imagined. But you have to be open to these possibilities and accept what life throws at you—the wonderful surprises and imperfections alike.

Speaking of California, there were many Western cultural flourishes throughout the film—the most prevalent of course being Estela’s taste in music. Why was it important to include those specific cultural touches?

Well as you know, this film is very autobiographical. I was always obsessed with music my whole life…

Which of course brings to mind your time at MTV Brasil…

That’s right, yes exactly! I was a VJ for them—but that was after. When I was a kid, a child I mean, I had these cousins that were crazy about The Beatles, so I grew up listening to their songs and by the time I was six or seven years old, I could sing “Hey Jude” and “Yellow Submarine” by heart although I didn’t know what they meant. And I learned a lot of English because I wanted to know what they were singing about, so I was always very much into music, and of course as a teenager I was collecting these records and I was completely into it—The Cure, The Smiths, you know—so I wanted the film to have these songs, but you know they’re very difficult to get cleared. It’s expensive, especially since we’re a small Brazilian production company, and I also absolutely needed a Bowie song because I was OBSESSED with him as a teenager—I was completely, completely crazy about him. I really did fall in love with him actually; you know I wanted to be his girlfriend [chuckles].

Was Brazil in general enamored with American culture at the time?

Well Brazil is big, I mean if you talk about—most of the population aren’t even exposed to the culture enough to know much about it. But yeah, we are kind of dominated by American culture one way or another through American music, films, American literature, everything—the world is dominated by American culture! [laughs] Especially films and music.

There are definitely some great subtle throwaways to these influences throughout the film; like little Easter eggs for those who picked up on such details. I loved how Estela wore a ‘tkts’ t-shirt in one scene for instance; that Broadway tribute was a nice little touch. Speaking of your muse, how did Clara Gallo get on board with the film?

She auditioned, but before that she had no acting experience at all—not film, theater, nothing. But she was very different, and she made me think of the character in a different way. When she came in for her audition, she had long hair with dreadlocks down to her waist, she was very you know, modern [chuckles]. And I knew that this girl was kind of shy, you know she was wearing these very big t-shirts—very much a quiet teenager. But she had something about her, like there was something she wanted to talk about but couldn’t so instead was holding it in; I felt very drawn to that. She intrigued me, that’s the word. By the time we began rehearsing—after she had her callback and went through a six-week training period with an acting coach—she was totally into her exercises, running around and screaming.

Are there any challenges to directing a narrative film that you don’t necessarily encounter with documentaries?

Well I only did one documentary, and that film came to me as a necessity. My father was a filmmaker—the documentary is about him—and he died when I was very young. And when I went to film school, I learned that all the things people would tell me in terms of him and his talent were not just the kind of generalized statements one makes when talking about an absent father. So that made me curious and prompted me to learn more about who he was, and I’m glad I had the film to show me that. I had the need to understand who this figure was: what were his thoughts and ideas, what kind of person was he—I was curious to know more about my father. Plus, I had his works and films as a kind of guide, so with this [personal project] I never really thought of myself as a documentarian. Though I have thought about making more documentaries, especially when I come across a subject that interests me. But even in film school, I always thought of myself as a fiction [narrative] filmmaker. They’re very different from each other.

Speaking of your father, the theme of family is one that strongly runs throughout CALIFORNIA as well. Would you say that making films is a way to help you sort of therapeutically negotiate your own understanding of your identity and past?

Oh yeah. Whenever you’re dealing with a certain mode of expression, eventually you’re going to talk about yourself in one way or another. Some people hide more, others expose themselves more—but all of us are influenced by what we like and how we were brought up. I think it’s impossible not to show who you are and where you come from if you’re [creatively] expressing yourself.

Given that men dominate the film & entertainment industry around the world, is there a market carved out for female filmmakers in Brazil—either through some kind of network or state-sponsored support?

You know, things are changing now. There has definitely been more awareness surrounding this issue especially in the last year and a half, which has opened up a [necessary] conservation regarding the industry’s lack of female representation—not just in directing, but acting as well. So I do think the situation is changing, but the first step of course is to be conscious of the problem. We do have a problem—everyone agrees on that—you know, we cannot just accept the fact that women make up more than fifty percent of the population, yet only fifteen or sixteen percent of the films shown in festivals around the world are directed by women. That’s not acceptable.

Are we saying then that women are not interested in making films? Hhm. So you know, we really have to make our way because this is ultimately a man’s world. So many people ask me “what advice do you have for other female filmmakers?” My response is “Go for it! No one is going to open the door for you.”

But even though this is a problem around the world, Brazil is not the worst place to be a female director nowadays; we do have many. It’s interesting because whenever I get asked who my favorite female directors are, or what my favorite films made by female directors are, I can’t help but think how few options there are to choose from. I mean, you can offhandedly count all the names of these directors and their films because there are so few. This has to change.

Would you consider this to be a feminist film, then? If not, how do you respond to that label?

Well it is a feminist film, if you think feminism is about equal opportunities. My crew for this film was all female, which is rare for Brazil and around the world really. Between my DP, production designer, costume designer, makeup artist, I was surrounded by women. But the thing is, I didn’t go into this film thinking that I wanted to have an all-female crew—that was never my particular intention—it just happened.

This film is very much about the female experience, female desires—I suppose subconsciously I needed these women around me so it kind of happened naturally. And this too will naturally happen if more women write scripts and helm the overall filmmaking process—not just in terms of production, or makeup, or the wardrobe department.

What movies did you directly draw inspiration from when making this film?

As a teenager, I was crazy about John Hughes—I told all the actors that they had to watch The Breakfast Club because they both explore issues regarding teen angst and the adolescent experience…

I can definitely see that! Not just through their thematic overlap of course, but also in the respective way each film quintessentially embodies the decade’s style and culture—right down to Estela’s Molly Ringwald-channeled coiffure.

[laughs] I really love every part of that film, especially the music. But I also really liked The Outsiders, so I watched a lot of those films.

So suffice it to say you were very into the glam-punk scene.

Oh yes.

What do you hope audiences will take away from the film when leaving the theater?

I’ve heard many different reactions and responses to the film. People who lived in the 80s and remember that time period come up to me and say how I brought them back to their own adolescence especially through the music, costumes, and other details that defined the period such as the cassettes and phones that were used. So in a way this is very much a film for the Gen X and early Gen Y generation, I think those in their 40s respond most to the film’s sense of nostalgia. But then I also have teenagers tell me “Oh, it’s great how this film seems to be about me. I also fell in lve with the wrong boy, yada yada,” so they identify with the characters and the story, although it’s a completely different time and place.

Echoing how the film is both specific and universal. That’s probably the best kind of feedback any artist can get—that feeling of “relatability”; having a connection to the work.

Yes. People connect to the film, so this is the best thing that can happen to a filmmaker.

Do you have any upcoming projects that we can look out for?

I’ll be acting in a film called Ballad of Return. And as a director, I have a couple of projects in development.

So do you prefer being in front of or behind the camera?

It’s different. I like both, but it’s funny because when you are doing something you think, “Oh, this is the thing I like to do more.” SO when I was acting I thought “This is great. I don’t have to do anything but me.”

It gives you that creative focus.

Exactly. I don’t know how these actors direct AND act AND produce. How do they do it all?!

But when you go home at the end of the day, what stays with you more emotionally?

Both. I mean, directing is a 24/7 lifestyle because you never rest. I mean, when you’re sleeping you’re thinking about it, you live for it. You don’t eat, you don’t have any time for yourself because you’re constantly thinking about this one project for months. It’s very intense, but also very fulfilling.

With acting, you have to give so much of yourself. You feel exhausted, but in an emotional way. Especially if you have a character that demands a lot like, as was the case with me. I had to be depressed, I had to cry and scream and fight and dance and be naked in front of a whole crew—whew. It was like an emotional rollercoaster. And I’m not a [conventionally] trained actress, so for me everything was too much. It was a bit overwhelming.

I think it was Kevin Spacey that said—or maybe it was Gary Oldman? I don’t know, some smart actor said “Every time I go back home to my family, I take my character for a walk around the block so I can just let him be and leave him there. And then I can go home and be myself.” ■

California was also selected to screen at the Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival’s Premiére Brasil Feature Competition, as well as the São Paulo International Film Festival.