In terms of sexuality, colonialism doesn’t leave a lot to be desired. Mexican artist Rurru Mipanochia is changing all of that. Reveling in the hotbed of gender and sexual emancipation of millennial Mexico City, the 27 year old artist exudes the joy of having the freedom to be whatever gender she wants, have sex with whomever she wants and, if she is labeled a slut or a whore by Catholicism’s repressive sexual mores, she states emphatically that she doesn’t care. She likes it.

Rurru’s exhibition Xochiquetzal: Erotismo y Procreation is a celebratory blend of pop art and Pre-Hispanic deities. In March 2017, the work was shown at ArtSpace Mexico, a Mexico City Gallery with a revolutionary agenda of promoting and honoring subversive bodies. Rurru’s series of pen and acrylic on paper certainly fulfill the gallery mandate. However, there is a deeper rupturing in the work than the audacious representations of unabashed sexual freedom. By merging Pre-Hispanic gods and goddesses with Mexican pop culture, Rurru not only explodes the shackles of Catholic sexuality, but her work also serves to contemporize Mexico’s neglected cultural ancestry. Through her joyful representations of a present day sexual liberation, Rurru popularizes Mexico’s buried past.

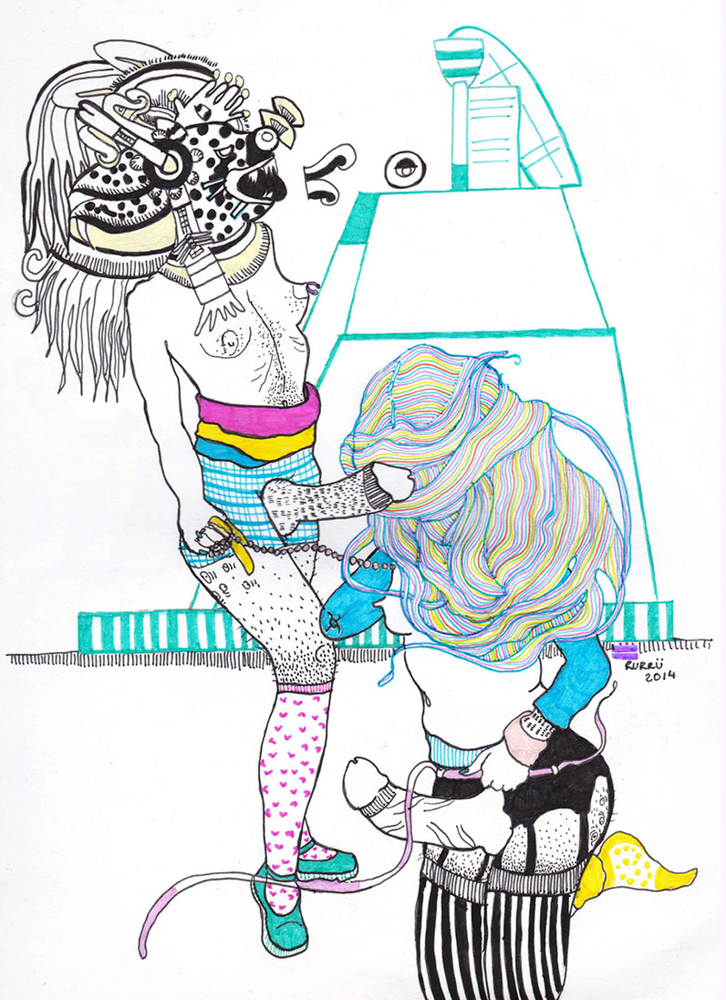

The artist told me how her paintings and drawings are self-portraits where she embodies her interpretations of the sexuality of Gods and Goddesses of Mexico’s Pre-Hispanic past. The connection of her own sexuality with the erotic symbols of her forgotten ancestry creates a timelessness that overrides any division between the past and the present. Rurru’s use of colour is both Mesoamerican and modern; she combines the tones from the past and pumps them up into a hyper-real playfulness of neons and pastels. The ferocious masks of the Gods and Goddesses are worn with classic Mary Jane shoes, rainbow soled platform sneakers and sweetheart patterned knee socks. The art is a resurgence and celebration of an oppressed erotic ontology through the sexual acts, attitude, fantasies and fashion of a not only liberated, but also irreverent, 21st Century Mexican woman.

Like Rurru’s penchant for not being tied down to any one gender, Xochiquetzal: Erotismo y Procreation is an expression of an erotic life with a shape-shifting sexuality. All the images exhibit an excessive androgyny. However, unlike a transgender desire to blend one’s one-or-the-other gender assignments, there is no subtlety in Rurru’s game of which gender is which. All of the figures are technically drawn as female; all have breasts, and yet, like the blatancy of many of her Pre-Hispanic ancestor’s sculptural representation of the penis, the majority of the images also sport male appendages verging on priapic status. Some of the cocks could be natural, some could be strapped on over-top of trendy fashion statements, and others look like they have been stuck in the crotch position with a suction cup. Some of the drawings are fully sexed female, but the hairy, wide-open representations of the vulva are a ready-made match for the stature of their male counterpart. Through the whimsical colour palette and the hyperbole of sexed male or female, the artist conjures an unsettling blend of humor and abjection where, through a symbology of excess, no sex or gender is one or the other.

The Mesoamerican Gods and Goddesses that Rurru brings back from the dead are connected to sexuality, sexual transgression, art, the earth and death. The work revolves around Xochiquetzal, the Goddess of not only flowers and art, but also of prostitution. Indeed, this correspondence of prostitution, flowers and art is in absolute contradiction to the master narrative of the West. By connecting the prostitute with such idyllic symbols demonstrates that, in the Mesoamerican culture, the erotic service was not damned as in Catholic sexuality or in the disparaging judgements against prostitution in 21st century secular culture, regardless of how much the services of prostitutes are indulged in by either hypocrisy. Like the artist herself, Xochiquetzal is a fierce and autonomous creature. Self-satisfied and relatively indifferent to the diminutive male to her left, Xochiquetzal’s legs are powerfully splayed and her hand digs into her vaginal core, about to pull out her innards or a well-fondled treasure, or both. This empowered and revered embodiment surfaces an ancestral past where sex for pleasure, without any connection to the procreation imbedded in the institution of marriage, is celebrated as art, or the highest form of human expression and how a force to be reckoned with is also a flower.

Two of the illustrations are of Tlazolteotl, the goddess of sexuality. In one, Tlazolteotl is an all-embracing libidinal force and a magnetic trajectory between the Pre-Hispanic past and Post-Colonial present. A be-sneakered autoerotic hermaphrodite, the heavy breasts droop as the erect penis reaches towards their cleavage. From the mouth of an almost imperceptible face spouts a watery beard, cornhusks hands waving in the background while the real hands are adorned with perfectly manicured, yet lethal, pink nails. In keeping with her play of apparent contradictions, the other representation of Tlazolteotl takes place in a stylized boudoir. Two beyond well-endowed females are fixed in a hyper-real state of pre-fuck, one with masked head thrown back already about to wail in ecstasy, the other mysterious in a swirling bondage hood made of candy ropes and a multi-coloured dye job.

In an act of superimposed rupture, Rurru’s bodies are imperfect. Not only are idealized female forms blatantly covered in hair, many of them are also missing a limb. The artist related to me how in the Nahuas culture, there was a relationship between sexual transgressions and defects in legs. In Rurru’s representation of Xolotl, the Dog God and God of Pleasure, the canine amputee is the aggressor and the instigator of the pleasure found in existing in the out-of-bounds titillation of sexual transgression. However, in absolute contrast with such bestiality, the Dog God is also scantily clad in a cotton candy blue G-string, thigh high fishnets and hot pink Go-Go boots. The tension produced by Rurru’s imagistic transgressions pull the viewer back and forth where it is impossible to settle between this and that. Human, animal, the idealized female form and the abject amputee are all one in her liberatory orgy.

Any pagan pantheon would not be complete without the Earth Mother and, in Xochiquetzal: Erotismo y Procreation, we are given two versions of the Aztec earth goddess, Tlaltecuhtli. Taking on male and female attributes, Tlaltecuhtli is typically represented as female and her name means “one who gives and devours life.” With the squatting life-giving stance and tongue that could be a flame or a root, Rurru keeps true to Tlaltecuhtli’s ferocity in keeping with the fertility and decomposition of the relentless life cycle. However, along with her popularization of these long-neglected ancestors, Rurru’s earth goddesses are psychedelic blasphemies that make the ferocity of life, death and sexual prowess just plain fun. In the first embodiment, the headdress could be made of robot sprockets and the giving and taking away tongue is a kaleidoscopic bong. The second re-introduces Tlaltecuhtli into contemporary consciousness as a globular monster straight out of Futurama who sits, legs splayed, birthing black gloop, on the edge of a plush sofa decorated with uncontainable filigrees. Both of Rurru’s creators and destroyers of the earth are kept company by serpents whose skin would make the most ecstatic jacket at any rave and are crowned by cartoony phases of the moon. In these Technicolor monstrosities, nothing is ever black and white.

In his study of the grotesque body of the Medieval and Early Renaissance carnival, Michel Bakhtin explains how “the grotesque body is not separated from the rest of the world. It is not a closed, completed unit; it is unfinished, outgrows itself and transgresses its own limits.” Indeed, the contradictions and impossibility of closure in Xochiquetzal: Erotismo y Procreation enter into the realm of the grotesque. However, unlike Bakhtin’s, Rurru’s grotesque bodies are not merely a ritual, an interval of blowing off steam after which the unmovable hierarchical class system was re-imposed. In her Mexican post-colonial context, where Catholic churches were literally built on top of Pre-Hispanic pyramids, Rurru’s ritualistic art extends beyond its frames; her illustrations impose the permanence of her oppressor’s erasure. As both irreverent artist and symbolic anthropologist, through her ecstatic acts of uncontainable sexuality, Rurru Mipanochia does nothing short of lopping the head off centuries of sexually oppressive colonial rule and, in so doing, giving new life to Mexico’s Pre-Hispanic past.

For more information please visit rurru.jimdo.com.

Support queer-run independent media and pre-order Issue 04 or purchase an annual membership. Membership includes a copy of Issue 04, special invitations to events, behind-the-scenes access to Posture, and more.