Sal Muñoz is an Artist and Social Justice Advocate who lives and works in New York City. He received his BA in Studio Art from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2012. Sal works in a variety of mediums examining issues of race, class, and sexuality.

Interview by: Annie Malamet

Photographs by: Joanna Moyer-Battick

A: Okay, so, tell me a little bit about your background and what brought you to activist art.

S: Well being an activist and being an artist both kind of started for me at the same time in high school. I grew up in California- and, back then, it was more global activism, a lot of international charity work, and my art work started with Photography… And, as I transitioned into college and I started examining my own identity more critically, I realized that both my activist work and my art work should be more focused- or I wanted it to be more focused on- issues that directly affected me. Because growing up as a low income person of color who was also queer, I realized that that was something that needed a lot of work.

A: you felt that that was being underrepresented in the art community?

S: Yes. Thank you.

A: Yeah, totally. It totally is. [both laugh]

A: What brings you to New York?

S: Well, I moved here a year ago, after I graduated college, to pursue more of an art career. And since I moved here, I’ve sort of been making art and having a few shows here and there. So I’ve been here about a year now and it’s all been pretty well so far.

A: Do you think that New York is inspiring you to make different kinds of work?

S: Yes. …Wherever you go you face these issues [of racism, classism, etc.], but I think they manifest very differently [here] from where I grew up, where I went to college-

A: In Santa Barbara?

S: Yeah. So, it’s changing the way that I think about these things and about the way that I want to address them. Another thing that’s really important in my practice is the work that I do with the Audre Lorde project. Because I feel like it’s one thing to talk about these things in very hypothetical, intellectualized conversations, but I feel like if you’re not actually on the streets trying to change these things then it’s sort of like an all-talk situation. And that, I find, has informed my practice a lot.

A: Do you think that you would describe your own work as falling under this- I don’t know if you’ve heard this term but it’s kind of a buzzword right now, the ‘umbrella of social practice’, which is inherently involved in tying in audience participation.

S: I don’t know if I would describe it as “social practice,” but I like when my work includes elements of audience participation, because I believe that it allows for the artwork to be expanded outside of the gallery. And a lot of the times my target audience isn’t someone who’s going to come to a gallery. And so for me that is something that’s really important, is taking art outside of this, you know, white cube gallery sacred space, and really bringing it to the people.

A: So, in a way, your work can maybe function as a critique of the gallery system itself.

S: Yeah, well at the same time playing into it. So, when I do have gallery shows, I try to invite my entire social network, and those are people who are not [in your typical] gallery audience.

A: Okay, what would you say is your ‘intended audience’? Like, ideally, who are the people who would be viewing your work?

S: Yeah, so it’s kind of twofold, and it depends on each piece, but sometimes I want my work to focus on validating the experiences of marginalized folks, and other times I want it to focus on sort of helping to educate over privileged folks. So it really just depends on the piece.

A: Okay, that makes sense. Can you describe the role of viewer participation in your work, for instance in your “Pull Yourself Up” piece, and the “Model Minority” piece, [which] really relies on audience participation.

Pull Yourself Up, 2013

S: Right, yeah, which is something that, again, is sort of hard in certain spaces. So… if you put those pieces in a gallery, there’s this wall that people feel like they’re not allowed to touch it, but as soon as the first person goes up and grabs it, then everybody starts taking from it. So really it’s just dependent on that one brave soul, or a plant [laughs], to go up and mess with it.

A: Yeah, so you would say that viewer participation is crucial, and essential, to the work that you produce.

S: Mm-hmm. To some of the pieces, yeah.

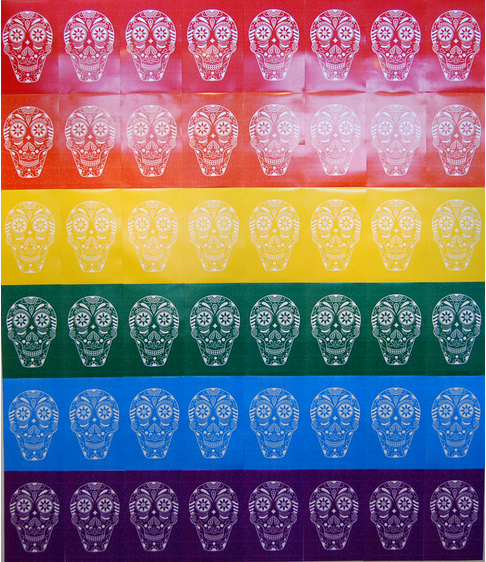

A: Well, I guess what I mean too is- for instance, with this piece [points to a series of printed skulls on the wall] – …in something like this, the whole point is that you’re getting that message out there, so the audience is super important.

S: Right, yeah. I mean, if nobody sees it, then it’s sort of- you know- what’s the point?

A: Your work deals with a lot of issues of intersectionality. You know, talking about kyriarchy, but also different mediums. Do you often feel pressured to define your art as one thing, say “I’m a painter, [or] I’m a sculptor.” And, additionally, do you feel the pressure of saying “I’m a Hispanic artist,” or like “I’m a queer artist”?

S: Right. So your question is kind of twofold, and I’m going to answer the first part first- I do feel like, when people find out, or when they ask me “Are you an artist?” or like the first question they ask you is “Oh, what kind of art do you do?” and for me that’s something that’s really hard to explain, because I do bounce around between a lot of different mediums. But I feel like that’s … part of what leads the success of my artwork, that the medium can fit what I think the message should convey. So I have my elevator speech prepared which is “I do a lot of things, but most of what I do is artist multiples, and photography, and graphic design.” But, I don’t want to limit myself, because I feel like, if I were to do so, I wouldn’t be able to address the wide variety of issues in the same way that I’m capable of when I balance it out between installation, and printmaking, and all those different things. And then, in terms of being forced to define myself as either a Hispanic artist or a queer artist, I think that my identity inherently informs my artwork, and that’s not something that I can separate, and that’s not something that I would want to separate, because… So much of my artwork reflects, and is based off of my identity, that I don’t really think they’re separable. But I also feel like my work can stand alone without relying on somebody having to know my full background and my full life story in order to comprehend or vibe with it. So, I wouldn’t want to be shoeboxed by only doing “Queer” art shows, or “Hispanic” art shows.

Intersections I, 2013

A: Yeah, cause [as an artist myself,] I find it often frustrating when people will say “Oh, you’re a feminist artist,” or whatever. But at the same time, that’s exactly what the work is about, and I’m not ashamed of it, you know…

S: Right, so I would never shun [a show for being “feminist” or whatever], but I think if I got into a pattern where I was only doing queer-based shows, I would take a serious look at what it is that I’m being accepted to, what I’m being asked to show…

A: Right, and exactly like what you were just saying, you want [different audiences] to see it.

S: Exactly.

A: So, are you more concerned with the aesthetics first, and then the overall message of it? Or are they completely intertwined for you?

S: They’re both intertwined. I don’t think you can separate one from the other without it becoming a bit of a mess. But I also think that- like, for me, and for how I work- I think of an issue I want to address, and then I think of how an art piece can address it, rather than the other way around… So that’s just sort of how I work, but I don’t think that, because I have had ideas that I think could [have a strong impact], but if they’re not executed properly or if the aesthetic isn’t addressed, then it’s unsuccessful, in my opinion.

A: Right, because people want to see pretty things.

S: Exactly, yeah.

A: Yeah. It’s interesting with activist art, because… I noticed on your website, you have a series of posters that you did, and you know, there are people who make posters who wouldn’t consider themselves “artists.”

S: Right.

A: …so what about your practice do you think distinguishes you as a “fine art” artist, (if you even think of yourself that way)?

S: Yeah [laughs]. I do consider myself an artist. I don’t know about a fine artist, but there are some folks who make very beautiful things but reject the idea of being an artist, and I think that that’s okay. But I personally do consider myself an artist. And… it’s funny because, I feel like I had this conversation all through undergrad-

A: Totally!

S: -yeah, about how my work is either too “activisty” or too “postery” to be considered [high art]. But I think that blurring the lines between what is “high” and “low” art is something that’s really interesting, that’s something that I do play around with in my work, as well as [with] who has access to those things. So, like, because I can run off a hundred of these, and it costs me like twenty bucks, does that make it less artistic? Does that make it less valuable? Does that matter?

A: Right. It’s also an interesting issue if you’re talking about class, because of [what you were just saying]; who has access to the work, and why shouldn’t it be considered art if everybody can see it?

S: Yeah. And I think also that putting a price tag on things definitely can become an issue if you’re in a fine art environment. Like, I had a show a while back where I priced these at fifteen dollars each, or two for twenty-five, because I think that’s an accessible price-

A: Right, and that’s important to your message.

S: -and they pushed me really hard to raise the prices. It was a very uncomfortable conversation. But I think it’s one that’s important to have.

A: Yeah, I mean, making the kind of work you make, in this white, elitist art world structure, can be pretty confusing.

S: Mm-hmm.

A: I understand why you’ve probably had this conversation a lot: because, you know, people are often against political work… From what I’ve seen on your website and from talking to you, it’s clear that there’s no guesswork when it comes to your art. You’re very up front about what the message is, and how the work is meant to be experienced. I find that interesting because I think that, in the art world, there’s a shying-away from giving too much to the viewer. And I’m curious how you feel about that in regards to your own work. And, [since] you take this approach of explaining everything up front, does that vibe with what you’re trying to say?

S: I think there’s definitely this idea that there has to be a lot of mystery and nuance to certain things, and this idea that a brush stroke can mean so much, if you only know what it means, etc. etc. I think that’s cool, but it’s not what I’m trying to do, because- and I talk a little bit about this in my artist statement- because I have such a specific message, and because I deal with such touchy subject matter, that I want it to be clear. That being said, I had this really great mentor who used the metaphor of a carrot in front of a mule: if it’s too close, then the audience isn’t doing the work that you want them to do. But if it’s too far, then nobody’s ever going to be able to get it. So I think there is definitely layers and subtext in my art that you can appreciate if you have that sort of [deep appreciation of art]. But, if you don’t, then you can still appreciate it for what you’re taking away from it.

A: It’s more accessible, yeah. I noticed that especially, and I think my favorite thing on your website was the “Pull Yourself Up” Piece, because I felt like you explain exactly how it’s meant to be experienced, but at the same time there’s a lot of nuance, there. Like: the cowboy boots are gold, –

S: Right, exactly.

A: -even just talking about the idea of the pushup [as a generic trope of masculinity]…

S: Yeah, exactly. And those are all things that were important to me that people could take from it. But it’s not 100% necessary.

A: Tell me about your work and practice. How do you conceive of a project, and how do you decide what the medium [might be]?

S: I think I touched on this a little earlier but to go more in-depth on it: I think about an issue that I want to address first, and then I think about how I can address that aesthetically, in a way that’s both visually appealing but also capable of getting my message across in a clear and concise way. I also take into account factors of accessibility and the target audience. I spend a lot of time writing, which I’ve noticed has really helped me to formulate concrete ideas a lot more… Like, do I want it to be widely disseminated, or do I want it to feel really small and personal and click with people on that level? Do I want it to be unexpected, etc. Does that answer your question?

A: Yeah, totally. It’s hard when you’re a studio artist, and you work in so many different mediums, because every medium has it’s own process and so on.

S: Yeah.

A: Do you do any performance with your work?

S: I don’t, because I have really bad stage fright, [laughs], but it is something that I think about constantly, and I think that it’s something that in the near future I will incorporate into my work. Right now I’m thinking of doing a video piece on code-switching. [It’s] a series of interviews with people on how it is that they change themselves in order to meet certain environmental expectations that are basic to their intrinsic survival. So, for me, when I go to work (in an office environment), I obviously don’t dress like this, I talk a little bit deeper; I’m a lot more smiley; … So, that being video, it would incorporate a lot more performance on my part, because I would want to include myself in that series.

A: What else are you working on now, and do you have any shows coming up?

S: Well, I recently moved and started a new job, so I’ve been trying to get all of that together before I jump back into making stuff and doing new shows. But right now I’m working on a series of posters that I want to hang up around the subways, that… addresses racial inequalities like “Stop & Frisk” and the rates at which people of color are stopped in comparison to white people, and I want them to imitate [the style of the MTA service change posters]. I [also] want to do more about the bootstraps myth, but I’m trying to think of ways to address that that are different from what I’ve done in the past.

Check out Sal’s website at www.salmunoz.com