Author | Sarah Fonseca

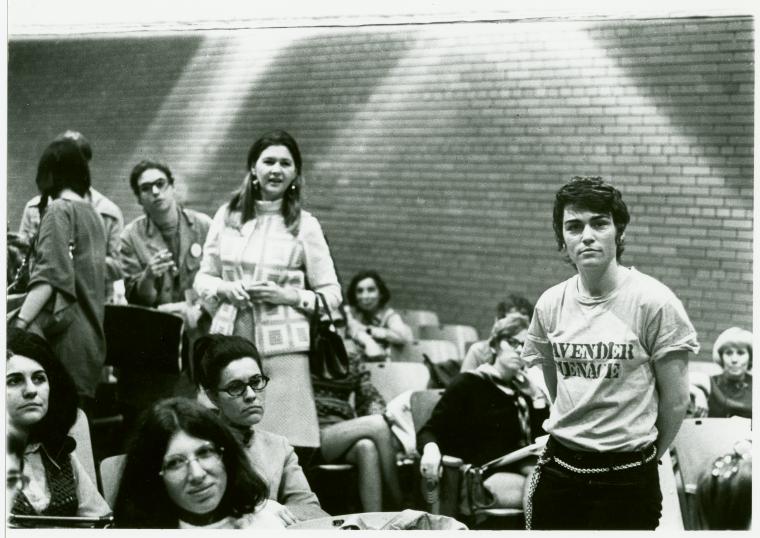

Featured image of Lavender Menace by Diana Davies

She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry is a new documentary that explores the women’s movement in the United States during its prime years, from 1966 to 1971. Transcending the photos of Gloria Steinem in aviator glasses and vague references to glass ceilings which frequently saturate Intro to Women’s Studies courses, the documentary is a loveletter to herstories lost and not-quite-well-enough remembered, from the illegal abortion providers of the Jane Collective in Chicago to the Puerto Rican women of the Young Lords in New York City.

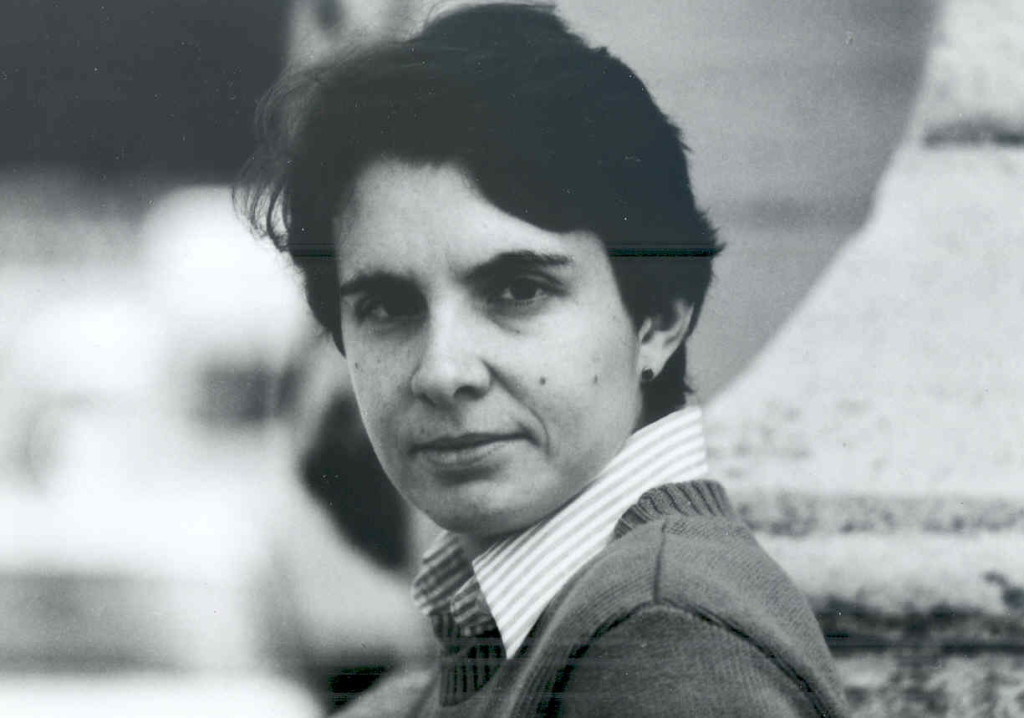

The director of She’s Beautiful, Mary Dore, was kind enough to sit down with Posture at She’s Beautiful headquarters in Brooklyn’s Old American Canning Factory. We talked about the struggles of funding a women’s documentary, the queer women of second wave feminism, and Cat Power.

The start of this for me was in 2012 when you guys did the Kickstarter for She’s Beautifuland it had vaguely slipped my mind until someone said, “Hey! Do you want to see this movie with me?” and I responded, “What? This came out so fast!” But the truth of the matter is that you’ve been working on this for—

[laughs] —a million years. I started writing grants before my kids were born—they’re 21 so that’s my easy date—and we couldn’t get funding. And of course I wasn’t sitting at home waiting; I’m a professional. So I took jobs, I raised my kids, then I would try every now and then and I would try and get nowhere. It was amazing that very liberal institutions were not up for it. It’s so interesting. I have really good contacts and a really good resume, and it was startling to me that this was so undesired. But this kind of proved a point that I got early, which is the women’s movement isn’t held in much respect—I don’t mean women in general, I mean the particular women who are covered in the film.

Was that your impetus for starting this project?

It was, actually, because I’ve made a lot of history films and labor films. I have a progressive bent, obviously. At some point you have one of those wake-up moments where it’s like, “How has no one made a great film about this?” You know, there are so many gay rights films. There are endless numbers of them and they’ve been made for decades. There have been docs on TV and there have been local PBS docs, and no one’s done a big, rabble-rousing evocative film.

Concerning gay docs: if they are women-centric, they don’t fly as well, they’re not as commercially successful. [Sarah] Shulman’s United in Anger talks about women within that movement, but it doesn’t have as big of a reach as other AIDS docs, unfortunately.

I think you’re right. I still haven’t seen How to Fight A Plague but I’ve heard the controversy surrounding that. I know lesbians were so prominent in [AIDS activist group] ACT-UP’s stuff. They were great warriors. And I guess they get downplayed, right?

What inspired the name?

I get no credit for that. We made a very sexy trailer in 2000, and we filmed the first four people, which luckily included [feminist writer] Ellen Willis. Of course wasn’t sick then; she died six years later. While we were doing research and looking for archival footage real quickly on the cheap with all our own money—so we couldn’t exactly do the deluxe production of the world—we found this Newsreel documentary from the late 60s. Newsreel was a radical group that covered anti-war stuff, covered everything. It was a part of the movement. They filmed a women’s street theater group who was doing this hilarious play. One woman was wearing a placard and a hat, pretending to be the big, fat capitalist, and another woman was being the president’s wife.

When we saw the film, it was hilarious—done in ancient black and white like a lot of footage in our film, by non-professionals to say the least—and the title was, She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry, and it was one of those “click” moments where [producer] Nancy Kennedy (who joined me as a partner on this in 2000; she’s a great editor and wanted to be involved) and I were, “What a genius title.” And we took it from them.

It is very fun. It’s very whiskey-drinking and attention-grabbing.

And it’s in-you-face! I never wanted to make a sentimental film. “Oh, it was all so lovely!” Because the women’s movement was very contentious. It was so in everyone’s face. It was so challenging to the women in it, as well as the people they were trying to convince that this was a good issue. So I thought it was really important to have that kind of presence.

Naturally, I have to ask you about the lesbians. [Author of Rubyfruit Jungle] Rita Mae Brown in particular—she’s such a spitfire. I’ve read her comments about the Betty Friedan “Lavender Menace” commentary and I didn’t know she was that actively involved.

She was very active for a few years. She wound up becoming a writer relatively soon. I don’t actually think she’s seen the film yet. I have to communicate with her, bizarrely, though her publicist. She doesn’t have Internet.

It was difficult?

It was difficult; I went through her publicist and graciously I did get the interview, which was great. And I had to go down to her farm down in Virginia and she was lovely. She spent the whole day with us, which was totally nice. She’s a real spark plug in the film. It was enjoyable.

I’d never heard of Karla Jay before.

Oh, you have to read her book! I’ll tell you a funny story about Karla Jay. She’s retired now, but she taught at Pace for a long time. I did not know her at all but years ago, somebody picked up this book called Tales of the Lavender Menace. It’s her biography. And it’s really spicy! It’s got lots of good sex scenes, and it’s really funny. Since we started cutting footage and getting everything together in 2000, in this amazing footage that Marlene Sanders had shot in the film, including that whole scene with the Ogle-In, and I always wanted to know who that mouthy woman was because I’d always loved the woman who was like, “What a chapeau!”

So I’m reading through Karla Jay’s book in the middle of the night and—because I had heard about her from other people, that she was an important lesbian activist in that era—all of a sudden, I was reading about this event she organized where they hooted and howled at men and I had that lightning moment where I realized, “Oh my god, this is Karla Jay!” I had to meet her. It was such a fortune because it’s not like, when you look at old footage, you know who people are.

And when you’re sitting down with this person today or watching footage of her in interview, it can be a bit of a surprise. “Really, this is that person from way-back-when?”

I know! She’s legally blind now, so it’s really hard for her. She came to our film festival premiere with her guide dog. She came to see the film a couple times, and her partner told her who was speaking [in the film]. She was great to interview and she is very smart. She loved so many people. She was in Redstockings and really close with Alex Schulman and all kinds of people. She wasn’t a star the way Rita Mae kind of made herself a star and, of course, pissed off people in doing so. It’s complicated. But when you make a film, you don’t care who likes each other or who doesn’t. You just choose who you think is best for the film, and thinking about your audience at all times.

I wanted to ask you about the contemporary soundtrack choices. I believe I heard some Le Tigre and Cat Power in there?

You did! Yeah, that was deliberate. One of my early interns was doing the Lavender Menace footage and she found that Cat Power song, “Free.” It was so perfect, and I thought, “Oh, this is so cool.” I always wanted to use popular music but I didn’t necessarily want it all to be from that period, but it had to have the same sort of similar tone for it—you can’t just throw together a mishmash of music. And there’s a lot of women artists from those decades whom I adored but couldn’t put in. I’m madly in love with Kristy Hinds but it had too much of an 80s feel. The Cat Power songs and the Le Tigre songs were kind of timeless, in a way, and they meshed with the old music.

Was there anything—be it video or audio—that broke your heart to leave out?

[laughs] Um, well, it broke my heart to keep the music that we’ve got because I’m still in debt for it! That’s the real heartbreaker. A lot of smart people said, “You should just trade out the great music ‘cause it’s gonna kill you financially.” It makes the film. You know, I wanted this film to reach a populous audience and I know that the music is really helpful. People have told me that they wish we would put out a CD to go with it because they get really revved up by the music. That was a fiscally irresponsible decision which I am still paying for.

Being that a majority of the film is retrospect, was it kind of tricky discussing contemporary issues?

It was difficult. I knew that we had to allude to what’s happening today, but my original purpose was very much to resurrect this history that I thought had been so neglected and denigrated to a degree where, you know, so many people I meet—even people who’ve been in women’s studies—the first words that come out of their mouths are racist, sexist, and elitist. And it’s like, you really don’t know the history of the movement if that’s what you believe because there’s room for all those criticisms but that’s not what you lead with. What you lead with is that it was the biggest social movement of the last century and that it had enormous impact despite its flaws.

That’s where I do think that it’s a sort of misogyny because it’s so interesting that every movement made mistakes but the women’s movement gets more trashed for it, interestingly enough. It’s so interesting.

Who’s your feminist icon?

You know, it’s funny, somebody asked me that and I said my grandmother, who was certainly not a feminist but she influenced me enormously. I don’t have one, you know. My feminist awakening was—in terms of the actual movement, I’m a little bit younger than the women in the film—and I was with the women from Our Bodies, Ourselves. They’re my heroes just because of what they did. They weren’t med students or scientific geniuses; they were ordinary women saying, “We know nothing about our bodies, this is ridiculous.” And they did it on their own. They bartered their way into medical libraries and became self-taught. It’s so admirable what they’ve done.

Locate a screening near you on the She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry website.