The artist and muse relationship is both a venerated and highly criticized motif in the history of art. Most familiar with art history are aware of the long, misogynist and racist tradition of male and white artists both venerating and exploiting their marginalized subjects. Scarlet Muse, a photography exhibit at Daniel Cooney Fine Art gallery in Chelsea, begs the same critique. Described as “an alluring look at the intimate relationship between photography and prostitution” ranging from 1850-present, the works included all utilize the sex worker subject as artist muse.

Entering the space, the viewer is overwhelmed by both the sheer volume of prints and the compositional thread that weaves them together. It is a familiar image: the (often naked) sex worker naturally posed in some timeless den of iniquity. It is not remarkable that the bodies on view are mostly queer, mostly female, mostly trans, and mostly of color, groups that are often disenfranchised and ostracized to the point where sex work is the best option for obtaining any quality of life. The collection is impressive, beautiful, and painful.

Photographs from Philip-Lorca diCrocia’s Hustlers series are on view, the most striking being a large-scale print of a young black man throwing his head back in laughter while blocking most of his face from the camera with his hand. Surrounding the photo are numerous inspirations for the diCorcia series, including Anthony Freidkin’s hustler portraits from the early 1970s, Danny Fields’ 70s snapshots of male prostitutes, and Larry Clark’s images of male hustlers from his 1981 book Teenage Lust. Equally inspired by these predecessors is a piece from Mary Ellen Mark’s famous series about a (white) 13-year-old street based prostitute named Tiny.

“Again the question of how those who wield privilege can make interesting work about marginalized people begs to be asked.”

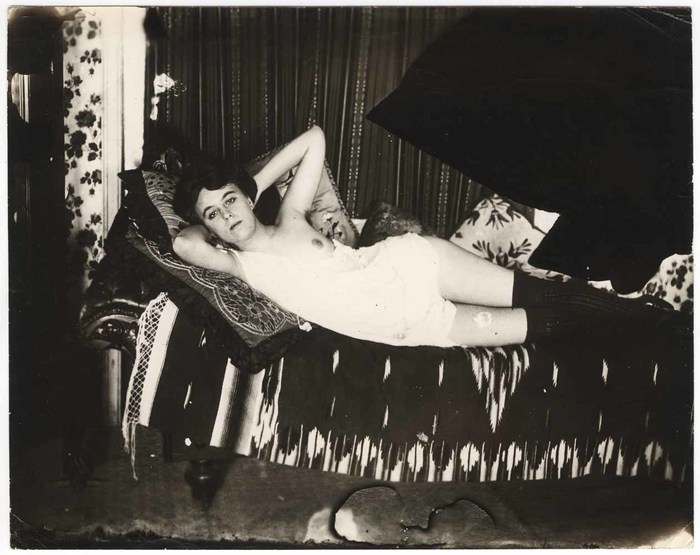

Each photograph’s inspiration can be traced to another just beside it. An E.J. Bellocq photograph from 1912 informs Jane Hilton’s Precious series from 2013, which documents brothel workers in Nevada. Christer Stromholm’s images of transgender sex workers in Paris in 1955 can be seen in Jeff Cowen’s series on the trans sex workers of the Meatpacking District in the 1980s, which in turn informs Chris Arnade’s 2012 photographs of prostitutes in the Bronx. Trans women as subjects occupy many of the works on view. An Amos Badertscher photography of a young, topless trans woman features hand written text describing a life taken too soon by AIDS in the early 90’s. Unfortunately, the text ends with a note on the subjects “real” name. Again, the question of how those who wield privilege can make interesting work about marginalized people begs to be asked.

The statement for Scarlet Muse pointedly notes that the exhibit is not “an exploration of otherness in an illicit and seedy world” but instead “reveals deep personal connections and great affection in ultimately loving relationships. While many of the photographs provide a glimpse into the most intimate activities they also tell stories of the individuals pictured and open a door to countless insights of human behavior.”

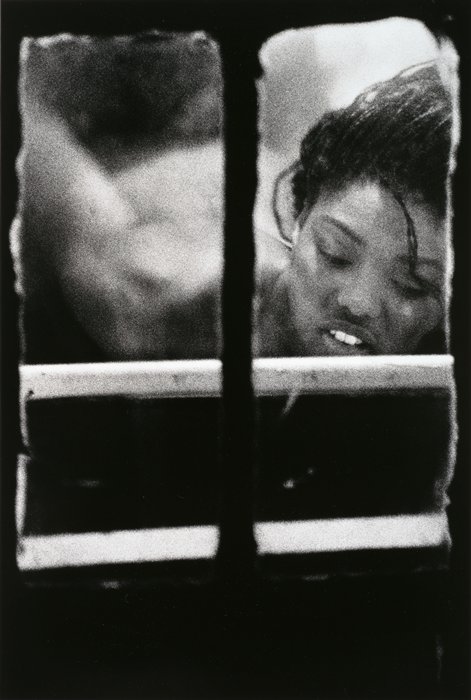

While the photographs are certainly intimate and striking, it is hard to see any insight into the subject’s lives beyond their trade. For example, the introduction to Jane Hilton’s Precious monograph (available to read in the gallery) describes her reverence, love, and respect for her subjects and a desire to show them as complex people. And yet, the images are the same ones we always see: a naked sex worker in their place of business, be it a brothel or a street corner. How can an image of a prostitute offer any complex understanding of the subject when the viewer is never presented with anything other than the sitter’s role in the sex industry? Are the ins-and-outs of their occupation all there is to the sex worker subject? How is a photograph that reiterates in both composition and context the subject’s maligned profession complicating any sort of narrative? An artist can proclaim that the photograph does not exist to titillate but if it does just that, the statement means nothing. These artists may love and venerate their subjects, but all that is produced is more of the same romantic trauma porn. Preferable is the most honest and exploitative photograph on view from Merry Alpern’s Dirty Windows series, taken non-consensually with a telephoto lens from across an airshaft, showing a woman of color sex worker mid-session at a Wall Street sex club.

“These artists may love and venerate their subjects, but all that is produced is more of the same romantic trauma porn.”

A question of accessibility arises as well. Would anyone like the people in these photographs be welcome at or know of Daniel Cooney gallery? It is almost tragically absurd to see a print featuring a drug addicted street worker priced at $3,500. Many sex workers can and do make considerable money and many are even art lovers (we are real, whole people after all), but wealthy workers are quite honestly in the minority. Most sex workers are average people who make an average wage. It is startlingly appropriate that the gallery is adjacent to the Chelsea-Elliott project houses on 26th street. What a perfect exemplification of how the excess, pretentiousness, and poverty of New York City exist side by side. Of course, none of the subjects will see any of this money, but that’s not to single out the artists (or collectors) in this particular show; these are larger questions for the art world in it’s entirety.

“It is a similar feeling to visiting the Metropolitan Museum as a woman and seeing yourself in so many beautiful naked women colliding with so many violent misogynist histories.”

If you view the exhibit as a sex worker, these questions will be ever present. It was exciting to see an actual sex worker perspective in the self-portraits by Benjamin Frederickson of him at work with his clients, though they were not the most formally compelling. The exhibit is both familiar and othering. It is a similar feeling to visiting the Metropolitan Museum as a woman and seeing yourself in so many beautiful naked women colliding with so many violent misogynist histories. What would an image that shows a sex worker as a complete person, beyond their tragedies and disenfranchisement, even look like? Almost every artist featured has expressed a desire, either in statement or interviews, to present their subject “more” than a sex worker, to lift them up. But sex workers do not need to be elevated or wept for by artists and viewers. There is nothing inherently praise worthy nor pitiable about prostitution, so neither approach is satisfactory in complicating the mainstream understanding of sex work. Empathy for the prostitute is perhaps where great art begins, but to stop short at such a basic gut reaction sells the subject short.

Scarlet Muse is now on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art on 508 W 26th Street, Suite #9C through July 22nd.