Because strong women are often considered lowbrow spectacles relegated to freak shows and bodybuilding championships that take place in rented-out hotel ballrooms, I’m inclined to look for us in highbrow places, particularly in art. It’s a hunger for visual representation that is only rivaled by the sapphic imagery I approached upon coming out. I needed to see that lurching mix of hurt and heat, the brush of lips, and that Pause between women, that conversational white space that whispered, “What an odd, sweet experience we’re having.”

[email protected] Pause that I now seek is is similar, but it’s located less in the pelvis and more in the lungs — in that deep breath of air a woman takes and holds before she stiffens her body in preparation for something physically difficult. In the weighted squat, the feral pose of childbirth experiences a metallic renaissance: it is now a sort of selfish labor where the woman, inhaling deeply under strain, is both mother and infant. The Pause is in the tensing of a tricep or oblique in a majestic pose during Miss Olympia. The Pause can also be found in the way muscle makes women’s curves, which are dictated by body fat, even more dramatic, rounding portions of the anatomy into punctuation marks. Yet despite the world containing many women who are the female equivalent of the nude, bulging Lysippos’ Farnese Hercules or the Rhodes’ Laocoön and His Sons, there are no Lysippos or Rhodes trio statues that resemble these women.

It took a queer from Long Island who had already effortlessly discarded gender ideals to create these missing masterpieces. With a woman as his subject, Robert Mapplethorpe probed deeper than the faggot flesh he photographed. In 1980, Mapplethorpe began documenting the first prominent American bodybuilder, Lisa Lyon, simultaneously concealing and magnifying what she was most known for, what all American women are known for in some fashion or another: her body. Hers just happened to be a body that won the first women’s bodybuilding world championship and could squat 265 pounds.

In the most recognizable image from the series, Lyon faces away from the camera, Whistler’s Mother-style. She wears a black leather leather dress and a veiled hat of the same color, her long brown hair tucked beneath it. In her lap, she holds her own hand, her right bicep tensing dramatically. A narrative of mourning, self-sufficiency, strength — one so tediously native to all forms of womanhood — is formed. There’s so much there; you can’t help but gluttonously want the rest. Mapplethorpe couldn’t, either. “I’m just as interested in her mind as I am her body,” he once remarked.

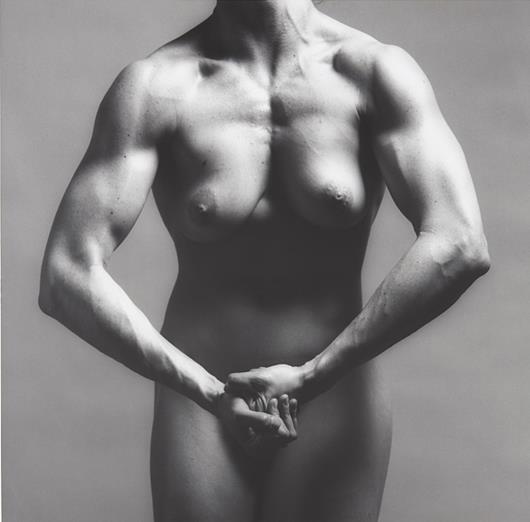

Still, it’s one of his undeniably explicit photos of Lyon that remains my favorite. She stands nude, facing the camera but her head is entirely cropped out, the portrait only including her body from her neck to her upper thighs. Sure, she’s just another woman reduced to her body. But unlike the colorful Playboy photoshoot Lyon did around two years prior, all smooth, oiled skin and elegant up-do in a leotard, she seems far less objectified here.

Once more, her hands are clasped together in front of her, this time in that quintessential bodybuilder pose that always makes me think, “Grrr.” You can distinguish the very place where the muscles in her chest reluctantly give way to the slope of her breasts, round nipples, another slope, and then return to the muscle of her ribs. Wherever the lamp highlights her skin, cords of vascularity are illuminated: her neck, her forearms, even her elbows (who knew we even had veins there?). And while her hands, tiny and massive at the same time, are pressed together directly in front of her mons pubis, her fingers are folded in a way that resembles a vulva, all hers.

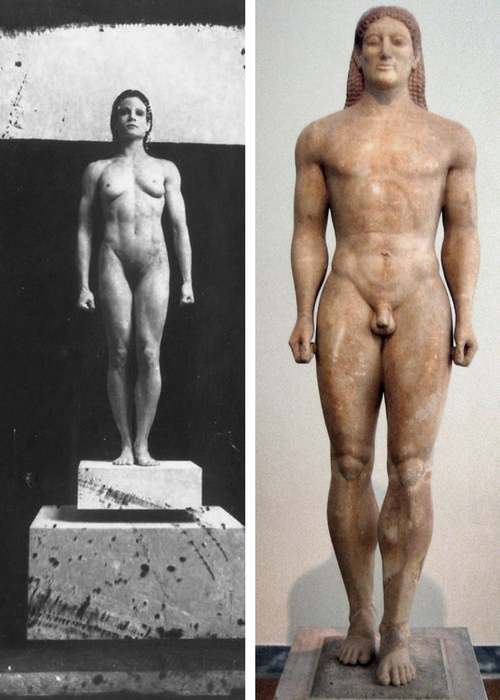

Lyon, like the rest of Mapplethorpe’s subjects, resembles a sculpture, frozen in the grey mortar of a gelatin silver print, rivaling the sculptures of the Greek bro greats. However, it wasn’t until 1983 that the mortar hardened. Joël-Peter Witkin, another New York artist with a penchant for capturing that which could be considered taboo, photographed Lyon as a literal sculpture, complete with a two-tier pedestal.

With fists gently balled at her sides and legs separated and bent to indicate a forward stride, Lyon is posed as Kroisos Kouros, an ancient statue that once protected the grave of a fallen Greek warrior. Factoring in Kroisos’ centuries of wear and tear and Lyon’s own disciplined diet and workout regimen, she is easily the more defined and intimidating of the two guards; she is the one I’m compelled to write into my last will and testament to be the guard of my own embalmed body.

In the mid-80s, when Frank Miller began writing a comic book inspired by mythology’s Electra, he took Lyon’s body in an entirely different direction, modeling his title character, Elektra, after her. And despite the way that medium — paper — seems far less strapping than stone, it was no less remarkable: a valued image of a powerful woman was finally begetting more images of a powerful woman.