Author | Geoff Mak

A review of the Zanele Muholi Isibonelo/Evidence exhibition at The Brooklyn Museum

“[Muholi’s work] straddles a line between art and activism that the curators themselves seemed uncomfortable with.”

The distinction between a work of art and pornography is a matter of visibility: who is watching, and why. Another distinction between art and pornography is that the latter exists for a purpose whereas the former does not. In Zanele Muholi’s video Being Scene, on display now at the Brooklyn Museum, two figures fuck: one dark, one not. The figures are blurred beyond the point of identification, though they appear anatomically female. One can hear their low voices acknowledging the camera, which suggests that they know they’re being watched. In twelve minutes, the forms embrace, turn, separate and conjoin to the sound of moaning, kissing, and static.

The video includes the artist herself and her lover, though perhaps even those details aren’t important. The title Being Scene is a gesture beyond identity—the women as South African, as queer lovers—and to a purer, more essential state of being. The title could also be read as “Being Seen,” which both invites and repels the viewer. While one cannot see them clearly, the viewer’s gaze is then redirected to a deeper, more truthful likeness: a “Being Scene,” one that exists for its own sake, too obtuse to get anyone off, inherently useless.

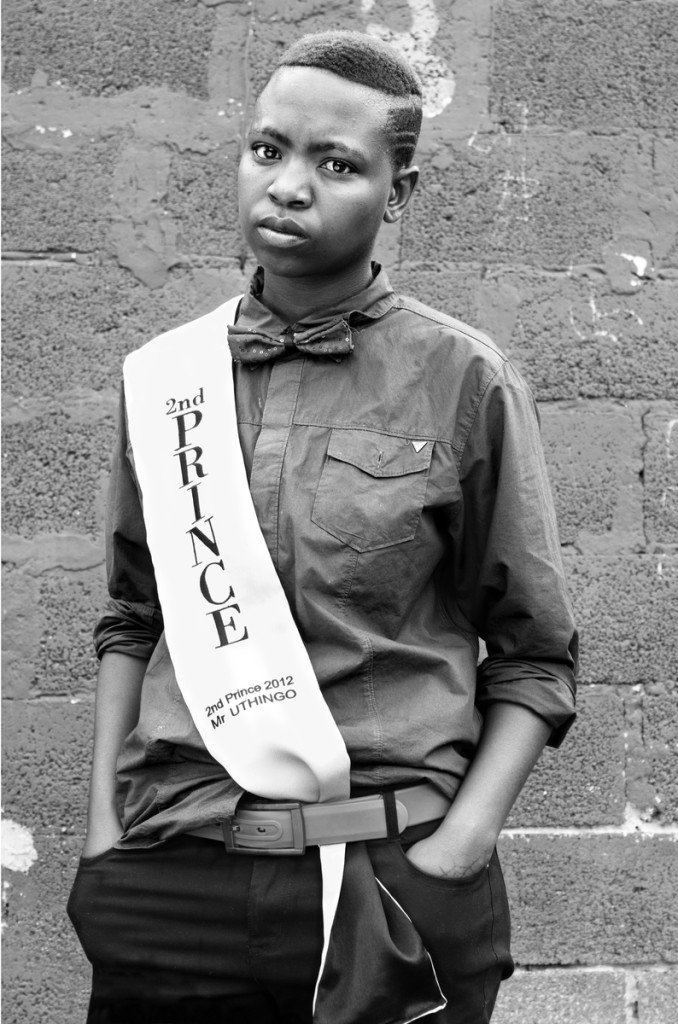

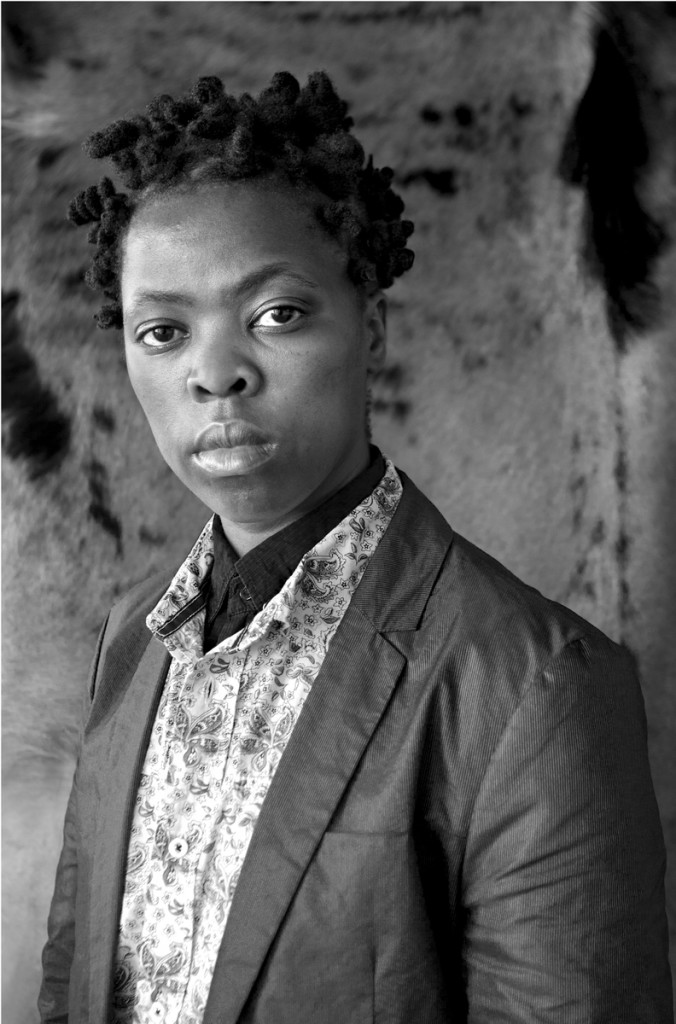

Being Scene is the only piece on display that I’m convinced is fully a work of art. It is also the best. The rest hover between art and what might be considered “visual activism,” a term Muholi uses to describe her own work. The major project of her career, which also takes center stage of the exhibition, is an ongoing series called Faces and Phases, which includes portraits of lesbian, trans, and queer women from South Africa, several of whom are victims of violent and fatal rape crimes.

When viewed as a whole, the effect is overwhelmingly compelling. The photos collectively make visible a full spectrum of queer life in South Africa. Like August Sander, Muholi photographed subjects across age and class. The subjects wear any number of styles, which repels the effort to mine visual similarities: streetwear, leopard print, cross necklaces, sweater vests. Each of the subjects looks directly into the camera, confronting the viewer’s gaze. They know they’re being watched.

Visibility here has a clear political agenda. Adjacent to the portraits is a black wall with hand-written quotes and descriptions, referring to South African rape crimes. One line reads: “She was only 19 when they stoned her to death in her township Khayelitsha. Her name was Zoliswa Ngkonyana.” It isn’t clear whether this woman was photographed by Muholi, which suggests that any one of the photographed could have been a victim. Justifiably, the installation is designed to provoke moral outrage, though perhaps at the cost of positioning Muholi’s subjects as passive victims, waiting to be saved.

I thought of American precedents to Muholi’s work who photographed with explicit political objectives in mind. Ansel Adams photographed Japanese families in internment camps, and Dorothea Lange photographed migrant workers during the Depression. Their work proved effective, or at least on the right side of history, while shown today as superior work from pioneers of the form. In 2015, a humanist portrait photographer is not a pioneer of the form, and as this exhibition seems to suggest, the lasting contribution of Muholi’s work is primarily political.

For works of art to be given an explicit political purpose, what happens to them once that purpose is achieved? Some of the pieces on view are particularly heavy-handed. Newspaper headlines of “curative rapes.” A sculpture of a coffin with a photograph of the deceased. It’s telling that Muholi identifies as a “visual activist,” not an artist. Posterity and aesthetic experimentation isn’t the objective here, and her work can’t be evaluated in those terms. But at the same time, this isn’t exactly “protest art” either. It straddles a line between art and activism that the curators themselves seemed uncomfortable with. As if to nudge Muholi’s work to the political side of the fence, the exhibition facilitates a clear-cut view of morality, an unambiguous breakdown of good and evil in which evil has the upper hand. We’re not supposed to leave the show contemplating the social complexities of representation, of censorship, or the relevance of photography in the digital age. We’re supposed to be outraged.

If anything, this show may very well be an indictment on the insularity of contemporary art world discourse: for what does theory or criticism matter to a lesbian woman raped and killed by her cousin. Many of the young women in Muholi’s photographs are dead. Who can fault someone for devoting her body of work to ending extreme violence against targeted minorities? But virtue aside, pornography and visual activism are uncomfortable cousins: they compel you to do something. And if they don’t, they fail.

For additional information visit The Brooklyn Museum’s website here.